Production

Production of The 24¢ 1918 Air Post Issue

4-10 May 1918—Design, Dies and Plates

10-12 May 1918—Printing

13-14 May 1918—Sale Days

Production of The 24¢ 1918 Air Post Issue

With the arrangements and start-up date for the new airmail service in place, Postmaster General Burleson realized that he did not have authority to establish a special airmail postage rate, a power reserved for Congress. On 28 March 1918 Senator Sheppard introduced a bill (S. 4208) authorizing the postmaster general to charge 24¢ per ounce for mail carried by airplane.

The bill passed and was signed by President Wilson on 10 May 1918, just five days before the first flights were set to take off from Washington, D.C., and New York City. Nearly one week earlier, on 4 May 1918, engravers at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) had already started working on the new stamp.

The story of the first airmail stamp’s design and production is also the story of the Inverted Jenny. While many facts are known, there remain several missing elements and uncertain answers to questions that were asked as soon as the Inverted Jenny was discovered on 14 May 1918.

4-10 May 1918—Design, Dies and Plates

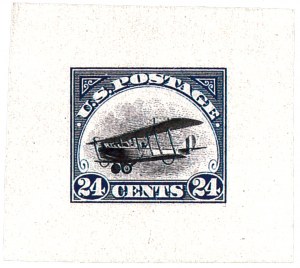

Back to TopThe new 24¢ airmail stamp was valid for regular postage, and regular stamps were valid for the special airmail service. Accordingly, the new airmail stamp was labeled “U.S. Postage” without any reference to its purpose other than the symbolic image of an airplane. It was printed in two colors, red and blue, which together with the white paper background created a patriotic color theme during World War I. As late as 9 May 1918, just a few days before the stamps were to go on sale, postal officials had still not decided whether the frame would be in red and plane in blue, or vice versa.

All of the work on the new airmail stamp was performed by the BEP. In 1894, over the protests of the American Bank Note Co., the BEP had been given the responsibility to manufacture postage stamps for the USPOD. The BEP also had responsibility for producing tax stamps and other forms of government securities, including currency and war bonds.

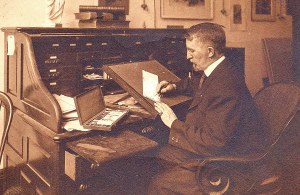

In 1918 the chief postage stamp designer for the BEP was Clair Aubrey Huston (1858-1938), whose portfolio consisted of numerous iconic designs, beginning with the 1903 2¢ Washington “Shield” stamp and including the long-running 1908-1922 Washington-Franklin (Third Bureau) series. Huston had also been responsible for designing the 20¢ Parcel Post stamp with an airplane vignette; it was created in 1912 and issued on 1 January 1913, at a time when the USPOD was lobbying Congress to allocate funds for the development of airmail service.

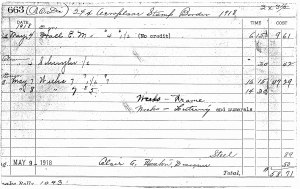

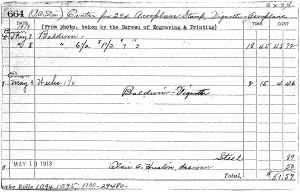

The BEP official die production records provide details of the work performed to complete the two separate dies for the 24¢ stamp (numbers 663 and 664): the dates and times of the work performed, a general description of the work, the name of each contributing engraver, and the amount charged to the USPOD for the BEP’s work (listed below). Images of the original cards are shown below the list. (provided by Joe R. Kirker).

Die 663 “24¢ Aeroplane Stamp Border 1918”

Die 664 “Center for 24¢ Aeroplane Stamp, Vignette-Aeroplane”

“(From photo. taken by the Bureau of Engraving & Printing)”

There is no official record of the date Huston began designing the 24¢ airmail stamp. He might have started before 4 May 1918, when Edward M. Hall (1862-1939) began preparing the frame die (the earliest entry on the card for Die 663). It was definitely before 7 May 1918, when a reduced stamp-size photograph of Huston’s design was submitted by James L. Wilmeth, the BEP director, to A. M. Dockery, the Third Assistant Postmaster General (the artist’s model for approval has never been located). The rapid pace of production required an informal expedited approval process, and the USPOD immediately green-lighted the BEP’s design.

Edward Weeks (1866-1960) began engraving the frame and lettering on the day the design was submitted for approval, 7 May 1918. Weeks finished the following day, 8 May 1918, the same day that work on the vignette die was started by Marcus W. Baldwin (1853-1925). Baldwin finished on 9 May 1918, and, as will be shown, Weeks made a small but significant contribution to the vignette after Baldwin engraved the plane.

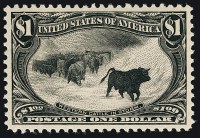

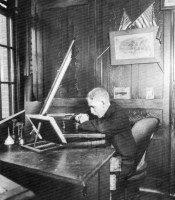

Baldwin, Hall and Weeks are pictured in the group photograph of BEP engravers shown at left. Another photograph of Baldwin at work is shown below. Baldwin was one of the BEP’s most accomplished engravers. His iconic engraving, the “Western Cattle in Storm” vignette on the 1898 $1 Trans-Mississippi (shown below), is considered to be one of the greatest masterpieces of American stamp art. Baldwin was 65 years old when he engraved the Jenny vignette for the new 24¢ airmail stamp. Hall was 56, and Weeks was 52.

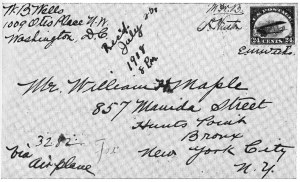

The signatures or initials of Huston, Baldwin and Weeks appear on a cover mailed by W. B. Wells in Washington, D.C., to William H. Maple in New York City (shown here). Since Hall was never credited by the BEP for his work on the 24¢ stamp, his signature was not sought.

Chronology of Production—The BEP records state that the War Department furnished a photograph of the plane for use in designing and engraving the stamp, That photograph has never been located or identified.

The plane pictured on the stamp is not one of the modified JN-4HM mail planes, which had the forward student pilot’s seat replaced by the mail compartment. With magnification, it is obvious that the plane has two seats: the forward cockpit is empty, and the pilot sits in the rear cockpit. Therefore, the photograph furnished by the War Department to the BEP was made from a standard JN-4 trainer, not one of the six planes specially manufactured for the airmail service.

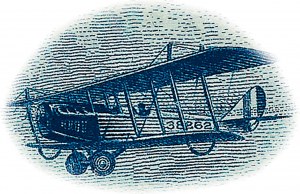

One detail of the plane engraving that has intrigued philatelists is the serial number on the fuselage. Number 38262 is the actual number assigned to one of the six mail planes purchased from the Curtiss company. In fact, it is the number of the first plane flown out of Washington, D.C., on 15 May 1918.

The question raised by this detail is how could the BEP designer and engravers incorporate number 38262 into the Jenny vignette before the planes were delivered to the U.S. Army’s airmail service on 13 May 1918? How could they know the serial number of any of the six planes, let alone the first one to depart from Washington, D.C.?

Based on the BEP record of die production and the facts known about the manufacture and delivery of the mail planes, a plausible sequence of events can be reconstructed. A quick review of the facts will be helpful before presenting a timeline.

On 30 April 1918 Maj. Reuben H. Fleet reported that the planes ordered from Curtiss had been built and would be shipped to the U.S. Army’s Hazelhurst aviation field near Mineola. A memorandum dated 8 May 1918 from Lieut. Col. R. M. Jones of the U.S. Army Equipment Division reported that the planes would be shipped on Sunday, 12 May 1918. The six unassembled Jennys were delivered in crates on Monday, 13 May 1918. The planes were numbered 37944, 38262, 38274, 38275, 38276 and 38278.

Assuming the stamp design submitted for approval on 7 May 1918 showed an airplane—any airplane—then Huston must have been given the photograph of a plane prior to that date. That is a safe assumption.

The plane in the engraving based on Huston’s model was an unmodified U.S. Army JN-4 trainer, not one of the six airmail planes, so the photograph could have been taken at any of the locations where Jenny trainers were used.

The serial number 38262 would not have appeared on the unmodified trainer with two seats. Therefore, the BEP must have been informed of the number before the die was completed. That could have taken place after 30 April 1918, the date Maj. Fleet reported the planes had been built, and before the vignette die was finished. Huston’s design model has never been reported or photographed, so we cannot know what number, if any, was on the plane in his original design.

However, it is possible to pinpoint the exact day the number was engraved on the plane, and identify the engraver responsible for doing it. That information might indicate when the BEP was informed that number 38262 was one of the airmail plane serial numbers.

According to the BEP records (the two cards shown previously), work preparing the frame die (Die 663) started on 4 May 1918. A total of 6 hours 45 minutes work was performed that day. The first entry (6h15m) records Edward M. Hall as the engraver, but he has never been given credit for the frame, and the words “No credit” actually appear in the record. The second entry on 4 May 1918 (30m) is for “cleaning” by another employee named Schuyler.

Hall was an accomplished engraver, who started working for the BEP in 1878 at the age of 16. Apparently, his only contribution to the creation of the 24¢ airmail stamp was to prepare the soft-metal die for the work that would be performed by Edward Weeks. Perhaps Hall started the engraving, using a frame design drawn by Huston.

The more important work in engraving the frame details and lettering was performed by Weeks on 7 and 8 May 1918. He worked 16h15m on the first day and 14h30m on the second day, for a total of 30h45m.

Marcus Baldwin started his work on the vignette (Die 664) on 8 May 1918. The BEP record shows just this date and a total of 18h45min. Baldwin’s diary states that he worked from 12:00 noon until 10:00 p.m. on 8 May 1918 and “all day” on 9 May 1918. For a 65-year old man hunched over a block of steel, these were extraordinarily long work days.

A significant but heretofore overlooked entry in the BEP record is dated 9 May 1918, the day that Baldwin finished his work on the Jenny vignette. This entry identifies Weeks as the engraver, spending 2h15m on the vignette die.

Baldwin’s diary entry for 9 May 1918 states “Mr. Weeks did the lettering.” This note has previously been misinterpreted by philatelists. Baldwin was not referring to the frame lettering; he was referring to the plane.

Baldwin has always been given full credit for the vignette engraving, and Weeks for the frame. However, the BEP entry for Weeks’ 2h15m work on the vignette and Baldwin’s diary notation, “Mr. Weeks did the lettering” are evidence that the serial number was engraved by Weeks, not Baldwin, on 9 May 1918, after Baldwin finished his engraving of the plane.

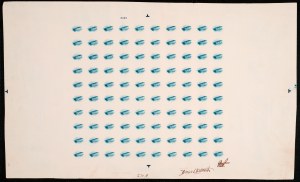

This date might be the actual day a serial number from one of the six mail planes was reported to the BEP, immediately following Lieut. Col. Jones’ 8 May 1918 memorandum that the planes were ready to be shipped.Before Weeks engraved the number on the plane, the BEP did something significant to document the progress of the die engraving. When Baldwin finished engraving the vignette on 9 May 1918, three die proof impressions of the frame and vignette together were made. One of these, in blue and black, is shown at right.

Significantly, this progressive die proof shows the Jenny without the serial number engraved on the fuselage.A letter dated 9 May 1918 from BEP director Wilmeth to Third Assistant Postmaster General Dockery enclosed “two proof impressions,” one with “blue background and red machine” and the other with “red background and blue machine.” The blue-and-black proof shown here was undoubtedly a third proof made at the same time, but not submitted for approval. This letter and the trial color proofs prove that the USPOD had still not chosen the final color scheme for the stamp on 9 May 1918, just days before the stamp’s issue date.

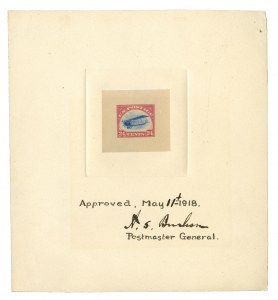

On 16 May 1918 the BEP sent two additional die proofs in the issued color combination to the Third Assistant Postmaster General’s office. Accompanying these proofs was a letter from Wilmeth to Dockery asking the USPOD to approve the final proof “as of date of May 11” (retroactively) and return it to the BEP. One of the proofs signed by Postmaster General Burleson and dated 11 May 1918 is shown at left. This proof has the serial number on the plane, unlike the blue-and-black proof made on 9 May 1918, before Weeks engraved the number.

The choice of 38262 for the stamp was most likely random and coincidental, since no one—not even the U.S. Army officials in charge of the mail service—ever said that 38262 was intended to be the plane to fly ceremoniously from Washington, D.C., on the first day. As explained in the History section, the last-minute assembly and positioning of the planes for the first flights was apparently done without concern for the serial numbers.

The two separate dies, once completed, had to be hardened for further use in manufacturing the plates. The frame die was the first to be hardened, on 9 May 1918, and the vignette die followed on 10 May 1918.

Making the Plates—In intaglio printing, the ink is held in recessed lines in the surface of the plate, and the printed image is transferred when the paper is forced against the plate under great pressure. This method of printing creates the slightly raised or embossed feel of the image or letters.

To produce a right-reading image on paper, a printing plate must have a mirror-image design. Therefore, if one were to examine the original 24¢ Jenny plates (vignette and frame), all of the designs would appear in mirror image. The plane would be flying to the right, and the letters and numbers would be reversed.

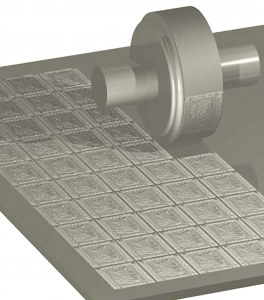

To create a plate of uniform subjects, an essential characteristic of high-quality security printing, a transfer roll is used to convey the original die design to each subject on the plate. The transfer roll is a cylindrical piece of steel, upon which a raised right-reading image of the design has been created from the mirror-image engraving on the die. When the transfer roll is rocked onto the plate under enormous pressure, it incises the design into the flat surface of the plate.

In simple terms, a hardened steel die produces the relief image on a softened steel transfer roll. The transfer roll is then hardened and applied to a softened steel plate. Finally, the plate is hardened to make it suitable for printing. The illustration at right shows the fundamental relationship between the transfer roll and plate subjects.

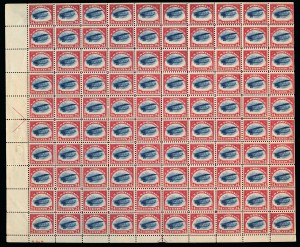

Two plates of 100 subjects (10 by 10) were used to print the 24¢ airmail stamp. Each plate number was engraved above one position in the top row. On a normal printed sheet with the top selvage intact, they are Position 4 (blue 8493—vignette) and Position 7 (red 8492—frame). On the Inverted Jenny sheet, the blue vignette plate number 8493 was printed in the margin below Position 97 in the bottom row.

The BEP craftsman responsible for transferring the design from the die to the plate via the transfer roll is known as a siderographer. The siderographer who made the 24¢ plates was Samuel De Binder, whose initials “S De B.” appear in red in the lower left corner of sheets produced before the BEP started trimming off the bottom margin. De Binder did not put his initials on the vignette plate.

Samuel De Binder, born in 1864, was 54 years old when he made the two plates for the first U.S. airmail stamp. He started working for the BEP in 1908 and made a total of 149 plates before retiring in 1929. His son Clyde also worked for the BEP as a plate finisher and siderographer. (Source: “Samuel and Clyde De Binder,” Rodney A. Juell and Doug D’Avino, United States Specialist, April 2005, digital version available at http://www.usstamps.org). According to an article by Clifford C. Cole (The American Philatelist, February 1982), De Binder used two separate three-subject transfer rolls—one with the vignette and the other with the frame—to make the two plates. The BEP records state that one transfer roll was made from the frame die and three rolls from the vignette die.

The process of applying pressure with levers and rocking the transfer roll over the plate with a hand wheel required considerable skill to achieve accuracy. The need for precision was even greater in making the two plates for bicolored printing, because the subjects on each plate had to be exactly aligned with each other, or the printed designs would be misaligned. To obtain proper alignment, De Binder made tiny dots on the vignette plate to space his entries at even intervals. The minute dots appear faintly on most of the stamps in a sheet. Another common practice was to use a plate subject as a guide for other relief entries by aligning one of the reliefs on the transfer roll with the recessed entry on the plate, then rocking the other two reliefs in their positions.

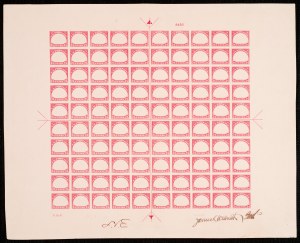

Despite De Binder’s skill and best efforts, there was still a slight variation that caused a shift in the alignment between the frames and the vignettes. On a perfectly aligned printed sheet, if the planes in the top row are centered within the frames, they begin to drift progressively downward toward the bottom of the sheet. The proof impressions from the frame and die plates, located at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum and shown here, confirm that the spacing was not precisely aligned between the two plates. This observation made from the proofs on card rules out the possibility that the misregistration found on printed sheets was caused by paper shrinkage during the printing process.

De Binder engraved his initials “S. De B.” at the lower right corner of the steel frame plate, which produced printed initials in the lower left corner of the sheet. The margin with De Binder’s initials was left intact on sheets from the first few days of printing, but after the word “Top” was added to the plate(s) and the sheet-trimming process was modified, his initials no longer appeared on sheets. Since the Inverted Jenny sheet comes from the early production and original trimming format, the “S De B.” initials are present on the unique Inverted Jenny corner-margin block of four.

The blue vignette plate number, which was normally removed from early-production sheets when the top was trimmed, appears in the bottom selvage of the Inverted Jenny sheet. The unique plate number block is shown here.

In addition to plate numbers and his initials, De Binder created guide lines on the frame plate. These vertical and horizontal guide lines divide the sheet into quarters and have arrow-shaped ends that appear in the selvage. The lines were printed in red between the fifth and sixth vertical columns, and between the fifth and sixth horizontal rows, creating crossed lines at the center, which produced the unique Inverted Jenny centerline block of four.

The frame plate also has small registration markers at the top and bottom. The same markers were put on the vignette plate at top and bottom, and they were used to check the alignment of the impressions (the alignment is correct when they precisely overlap).

On the vignette plate there are additional registration markers at the sides, a few inches from the stamp subjects. These were not meant to be printed, but were used by the printer’s assistant to align a sheet of paper with the printed frame impression with the vignette plate for the second impression.

10-12 May 1918—Printing

Back to TopDespite the Inverted Jenny stamp’s fame and the attention paid to it at the time of issue, right from the beginning there has been misinformation, misunderstanding and disagreement about how the error occurred.

The potential for a printing error was anticipated as soon as the USPOD announced that the first airmail stamp would be bicolored. The Inverted Jenny’s discoverer, William T. Robey, was familiar with the inverts that occurred during production of the bicolored 1901 Pan-American Issue. Before 14 May 1918, Robey wrote to a fellow collector, expressing hope that he might find inverts at the post office when he bought the new airmail stamp.

To determine the most plausible scenario for how the Inverted Jenny occurred, a quick overview of the printing process will be helpful.

Printing Method—Intaglio printing on a hand-operated press is extremely labor intensive. Printing each sheet involves multiple steps, enumerated below, and these steps must be repeated for bicolored printing, with extra attention required to ensure precise alignment of the two impressions.

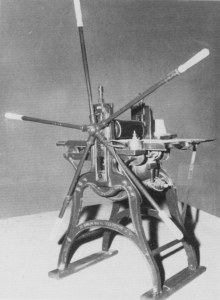

Because the BEP was under enormous pressure to print large quantities of wartime tax stamps, bonds and other securities, the bicolored airmail stamps were printed on an old Spider Press, so named because the hand-operated turning wheel has long handles that resemble the legs of a spider. A photograph of a Spider Press is shown here, and additional information about its operation may be found on the Smithsonian National Postal Museum website (http://postalmuseum.si.edu/collections/object-spotlight/spider-press.html).

- Remove the plate from the press bed and warm it to allow the ink to spread more evenly

- Apply ink to the plate and wipe the non-printing surface clean

- Return the plate to the press bed

- Dampen the paper and carefully position the sheet on the press (this is done by the printer’s assistant, whose hands are kept clean)

- Apply mechanical pressure to create the impression

- After the impression is made, remove the sheet from the press and stack it for inspection and additional production steps.

Trimming—At this point it will be helpful to repeat that the printed sheets of the 24¢ airmail stamp were originally trimmed at the top and right, cutting off the plate numbers at the top and the guide arrow at the right (as shown in the photograph below right). This was done to make the sheets fit into post office drawers. It was accomplished by substituting a cutting knife for one of the perforating wheels on the perforating machine. As the sheet was perforated, the cutting wheel trimmed off the excess margin.

A tiny telltale characteristic of the perforating mechanism used to perforate and trim the 24¢ sheets is a single missing pin in the fourth vertical line of perforations. This defect appears as a “blind” (missing) perforation between the third and fourth columns of stamps (its position from top to bottom varies). It is found on Positions 63 and 64 from the Inverted Jenny sheet (shown here). On some sheets, it is transposed and appears between the seventh and eighth columns, indicating a 180-degree change in orientation of the printed sheet and perforating wheels. The missing perforation was apparently repaired at a later point, since it is not present on some sheets.

The intact sheet selvage on early-production sheets has the guide arrows at the left and bottom, and the siderographer’s initials at the bottom left, but no plate numbers. This trimming characteristic of early-production sheets is a factor in determining how the error might have occurred.

The straight edges at the top and right of early-production sheets are typical of panes of 100 stamps from 400-stamp sheets. For this reason, when the Inverted Jenny error was discovered, it was assumed that the sheet came from a 400-subject plate on one of the BEP’s regular presses. Philatelists at the time widely assumed that three other panes of Inverted Jenny errors, cut from the same sheet, were lurking in post offices.

Inversion Error—Given the steps and handling necessary to print a sheet of bicolored stamps on the hand-operated Spider Press, is it possible to determine who made the mistake and how it happened? Unfortunately, not with certainty.

The order of printing was frame first, then vignette. Therefore, sheets with freshly-printed frames would be stacked by the printer’s assistant, checked for defects, counted and returned to the press for the second run of vignette impressions.

Because the frames were printed first, there has never been any doubt that the Inverted Jenny stamps are “center inverted” errors, not “frame inverted.” However, did the inversion occur because the sheet of paper was turned around 180 degrees? Or, after the vignette plate was removed, warmed and inked, did the plate printer put it back in a 180-degree rotated position?

Official reports and philatelists in general have leaned toward the inverted paper theory, but certain aspects of production actually tip the scale in favor of the inverted plate theory.

Since the sheets were checked after the first pass on the frame plate, the stack of sheets with frame impressions should have been in order and consistently orientated. The printer’s assistant had to remove each sheet, dampen it for printing, and carefully position it on the plate, using the two wide-set guides for visual alignment. After the printer made the impression, the sheet would be removed and stacked for drying, pressing and gumming.

In the inverted sheet scenario, the printer’s assistant—the only one with clean hands who handled the actual paper—would have to rotate the sheet 180 degrees before it was placed on the plate. Then, the same sheet would have to be rotated 180 degrees again before perforating and trimming. Unless the invert sheet was rotated a second time, the straight edges would be at the bottom and left, rather than the top and right (looking at the sheet with the red frame upright).

The missing perforation found between the third and fourth columns (Positions 63 and 64) of the Inverted Jenny sheet is further evidence that the sheet’s orientation was consistent with others with the straight edges at top and right.

Therefore, if one accepts the inverted sheet theory, then the Inverted Jenny sheet sold to Robey was rotated 180 degrees twice: once before the blue vignette printing, and again before the perforating and trimming process (gum was applied between printing/drying/pressing and perforating/trimming).

On the other hand, the inverted plate theory eliminates the need for a double-rotation of the paper. In this scenario, after the vignette plate had been removed from the press, warmed, inked and wiped, the plate printer put it back on the press rotated 180 degrees from its normal orientation. While this seems an unlikely mistake for a skilled BEP printer to make, there are a few factors that weigh in favor of a plate rotation error.

First, the design of the plane vignette does not have a clearly defined top and bottom in its shape and appearance. In fact, in 1918 very few people had even seen an actual airplane, so its appearance was unfamiliar. Obviously, the printed Inverted Jenny sheet escaped detection during the handling and inspection steps that followed the printing error. Therefore, it is conceivable that a plate printer, looking at a steel printing plate on the press bed, would not instinctively notice the inverted orientation of the planes.

Second, the plate itself did not have any distinguishing marks to indicate top or bottom, other than the small plate number at the top. Due to their symmetry, the registration markers at top and bottom and wide-set markers at the sides would not provide a visual cue. As far as anyone knows or has reported, the plate did not have notches or another structural feature that would prevent placement on the press bed with a 180-degree rotation.

If, in fact, the sheet of paper remained correctly orientated throughout the entire process, then the invert sheet Robey purchased was the result of the plate printer’s mistake, and it escaped detection during the inspection process and handling further down the production line.

Printings—Another technical matter that generates some controversy among philatelic specialists is the division of 1918 24¢ airmail stamp production into first, second and third printings. The three-printings concept evolved from the plate alterations, but no records have been found to support the division of production into three separate printings. Some argue that the three-printings concept distorts the events as they actually unfolded. Therefore, rather than dwell on how many printings there were, an explanation of what makes the stamps produced different is more helpful.

There is no argument over the dates and characteristics of the earliest sheets printed and issued. According to BEP records, the frame plate 8492 was put on the press on Friday, 10 May 1918. At this point, the frame plate had only a plate number at the top (above Position 7 on the printed sheet) and the “S De B.” initials at bottom left.

A supply of sheets with red frame impressions—the exact number is not known—was ready for the second run on Saturday, 11 May 1918, at 4:00 p.m., when the vignette plate 8493 was put on the press (source: Amick, JENNY!, page 28). The vignette plate had only the plate number (above Position 4).

It is not known if BEP employees worked on Sunday, 12 May 1918, but by Monday, 13 May 1918, a supply of fully gummed and perforated sheets is reported to have reached the main post office in Washington, D.C.

[Even on this point, philatelists disagree. Some claim that no stamps were available on Monday, 13 May 1918, and that the true first day of sale was Tuesday, 14 May 1918, when the stamps went on sale in the three principal airmail route cities: Washington, Philadelphia and New York. That is the day Robey bought the Inverted Jenny sheet at the New York Avenue office in Washington, D.C.]

The discovery of the invert error on 14 May 1918 was immediately reported to postal officials on the same day. The next day, 15 May 1918, as the inaugural flights were taking off, the BEP took its first step toward preventing the same mistake from reoccurring. To facilitate inspection and make it easier to spot a sheet with the vignette printed upside down, the word “Top” was added to the vignette plate 8493 above Position 3. The trimming procedure was also changed to leave the top selvage and plate imprints intact.

Sheets printed from the modified vignette plate in combination with impressions from the unmodified frame plate have just the blue “Top” and are known to collectors as “Blue Top Only” plate imprints. A Blue Top Only imprint is shown here.

All of the Blue Top Only sheets have the top selvage intact and a straight edge at bottom. The majority of Blue Top Only sheets or multiples have a straight edge at the left and arrow margin at the right, and the blind perforation is between the seventh and eighth columns, which is the opposite of the first trimming format. This indicates a 180-degree change in orientation between the sheet and the perforation.

However, sometime during production of the Blue Top Only sheets, another 180-degree change in orientation must have occurred. On some Blue Top Only sheets and plate blocks, the straight edge at the side is on the right, not the left, as it was on the first sheets produced. The missing perforation also moves from the seventh/eighth columns to the third/fourth columns (again, as it was on the first sheet produced). The Double Top sheets always have the arrow on the left and straight edge on the right.

The next plate alteration was the addition of the word “Top” to the frame plate 8492 above Position 8. Interestingly, the fonts used for the frame and vignette plates are not the same, which suggests they were done at different times by different BEP employees.

When sheets printed from the modified frame plate were placed on the press with the modified vignette plate, the “Double Top” sheets were produced. The vast majority of 24¢ sheets were the Double Top imprint variety. They are consistently trimmed with the straight edge at right and arrow at left. Some have the blind perforation hole, and some do not.

Returning to the debate about multiple printings, some specialists classify the three types of sheets as first, second and third printings. This classification implies that the supply of sheets without the “Top” came from a printing that had a beginning and end. Then, the vignette plate was modified by adding the word “Top,” and a second printing occurred with a start and finish. Finally, the frame plate was modified by adding “Top,” and a third printing took place. Three versions, three printings.

Other specialists have challenged this classification and chronology. They say the more likely scenario is that a supply of frame sheets was printed on the first two days of production, 10 May and the morning of 11 May. At 350 sheets per day, the total number of frame sheets without the “Top” imprint would be less than 700. Then, on 11 May at 4:00 p.m., the BEP started printing sheets from the vignette plate. By 12 or 13 May, a small supply of bicolored sheets printed from the unmodified plates—no more than a few hundred—was gummed, perforated and packed for distribution, reaching all three cities for sale on 14 May (and possibly one day earlier at the Washington, D.C., main post office). Included among these early-production sheets was the Inverted Jenny sheet Robey purchased on 14 May 1918.

In this scenario, when the BEP halted production, a stack of sheets with frame impressions only, without the red “Top,” was still awaiting the second stage of printing. Once the vignette plate was modified on 15 May 1918 with the addition of the word “Top,” the frame sheets without the word “Top” were put on the press.

It seems logical that the BEP, rather than discard valuable and needed product, simply used up the existing supply of frame sheets. Even if they knew the word “Top” would be added to the frame plate before more sheets were printed, they would still use the previously-printed sheets.

Finally, when the supply of frame sheets (without “Top”) was exhausted, the modified frame plate with “Top” was put back on the press, and the next group of sheets produced had the Double Top imprint.

The 24¢ Air Post stamp was current for only two months before the airmail rate was lowered to 16¢ and a new stamp was issued in July 1918. In total, 2,198,600 stamps were printed, and 2,134,988 were distributed. A director of the BEP reported to Philip H. Ward, a Philadelphia stamp dealer, that eight other invert error sheets were detected and destroyed. Only one out of approximately 22,000 sheets ever reached the public.

13-14 May 1918—Sale Days

Back to TopThe philosophical thought experiment — If a tree falls in the forest, and no one is around to hear it, does it make noise? — has a philatelic corollary.

If the 24¢ airmail stamps went on sale at the main post office in Washington, D.C., on Monday, 13 May 1918, but no one knew about it in advance or bought them, is that day the true first day of sale?

Specialists have engaged in vigorous debates over which day the stamps actually went on sale — 13 or 14 May 1918 — and in the absence of a preponderance of evidence to support one position or the other, it becomes a matter of interpretation and conjecture. The irony of the “first day” debate is that once the 13 May 1918 date was introduced into the historical record, the total absence of 24¢ Air Post covers postmarked on that day was remedied by forgers who produced covers and cards with the coveted 13 May 1918 postal markings. (To simplify the narrative, any general reference to the covers and cards will identify them as “covers.”)

Some of these fake First Day covers were accepted into the collecting community, and a few even received certificates attesting to their genuineness from well-respected expert committees. At least one major collection still contains a 13 May 1918 card, along with the 6¢ and 16¢ first day covers. These items have excellent provenance (ex Philip Silver) and certificates from The Philatelic Foundation, but unfortunately they have been denounced as fakes by the leading researchers in the field (Joe R. Kirker and Ken Lawrence). It seems unlikely they will be authenticated again.

In fact, not one genuine 13 May 1918 cover with the 24¢ Air Post stamp is known. Further, some specialists question whether any of the stamps were actually sold on that day. If any of the stamps were sold on Monday, they could only have been bought at the main post office in Washington, D.C. It was not until Tuesday, 14 May, that the stamps went on sale at other post offices in the District of Columbia and in the two other principal airmail route cities, Philadelphia and New York.

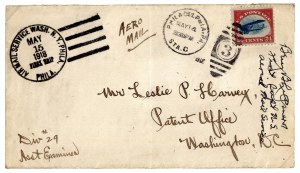

Image: Don David Price

The USPOD put the stamps on sale one day ahead of the scheduled first flights, so that the public could buy them and prepare covers for mailing on 15 May 1918. Most of the covers carried on the 1918 airmail flights only have the special datestamp and bars cancellation, which was struck from a single “duplex” device. This marking was made for use in the three cities by customizing the devices with the names of Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and New York. An example of this special airmail datestamp with the “First Trip” designation is shown here on a cover that was first postmarked at the Philadelphia Station C post office on 14 May 1918. This is a First Day of Sale cover—the first day the stamps went on sale in Philadelphia—and it is probably the earliest date that will ever be found.

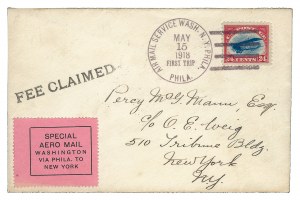

Another cover with the special airmail datestamp is shown below. It has the Philadelphia “First Trip” datestamp and a privately-produced label found only on covers originating in Philadelphia. The cover is self-addressed by Percy McGraw Mann, who was involved in the sale of Robey’s sheet.

Back to Top