Discovery of the Inverted Jenny

Before 14 May 1918—Robey’s Hunch

14 May 1918—Fate and Fortune

14-19 May 1918—Dealer to Dealer

19-21 May 1918—Sold!

1918—The Colonel’s Inverts

Before 14 May 1918—Robey’s Hunch

On 10 May 1918, just days before the new airmail stamps were put on sale, William T. Robey (circa 1889-1949), a stamp collector and employee of the Washington, D.C., brokerage firm W. B. Hibbs and Company, wrote to his friend and fellow collector, Malcolm H. Ganser. Robey had read the USPOD announcement of the new airmail issue and presciently gave Ganser the heads up: “It might interest you to know that there are two parts to the design, one an insert into the other, like the Pan-American issues. I think it would pay to be on the lookout for inverts on account of this.”

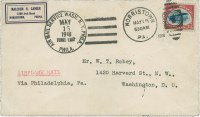

On 14 May Ganser bought some of the new airmail stamps in Philadelphia, but they were all correctly printed. He used one on a cover addressed to Robey, which was postmarked early in the morning on 15 May at the Ganser’s hometown post office in Norristown, Pa., then carried on the inaugural southbound flight from Philadelphia (shown below). By the time the plane took off in the afternoon of 15 May, Ganser already knew of his friend Robey’s great discovery.

While Robey sat in his office on Friday, 10 May, dreaming about the possibility of finding an invert at the post office, the vignette plate was already on the press several blocks south at the Bureau of Engraving & Printing. Over the weekend and on Monday, 13 May, sheets were being printed, gummed, perforated and trimmed. Among those sheets from the first few of days of production was the object of Robey’s dreams, the Inverted Jenny.

14 May 1918—Fate and Fortune

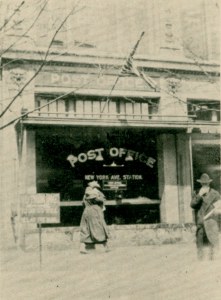

Back to TopRobey’s employer, the brokerage firm of Hibbs and Company, was located at 725 15th Street N.W. in downtown Washington, D.C. (now called the Folger Building). The New York Avenue branch post office was located just a few minutes away on foot, at 1317 New York Avenue. Early in the morning of Tuesday, 14 May, Robey walked to the post office with $30 he had withdrawn from his account. There are conflicting accounts from Robey about what happened that day, but the most plausible recollection is that he was dissatisfied with the centering of the few sheets the clerk had available in the morning, and, after being told a fresh supply was expected, he returned at noon.

As Robey recounted in 1938 in an article he wrote for the Weekly Philatelic Gossip, the same clerk was on duty when Robey returned at noon. When asked if new sheets had arrived, the clerk reached down under the counter and offered a full sheet. Robey immediately recognized that the planes were flying upside down. He described his feelings at that moment: “my heart stood still... it was the thrill that comes once in a lifetime.”

Robey promptly paid $24 for the sheet without disclosing the error. He asked if the clerk had any more and was shown three other sheets, all normal. At that point Robey revealed the upside-down airplane errors to the clerk, who urgently left his window to make a telephone call. Concerned that his sheet might be confiscated, Robey left and walked to the Eleventh Street branch office to see if any other errors might be there. He found none and then returned to the Hibbs office to tell his co-workers and notify collector friends and dealers of his discovery.

Robey sent telegrams to a few collectors and dealers in New York and Philadelphia, alerting them that he had discovered an invert error and, for whatever reason, giving them the plate number that was visible on the bottom of the sheet (the top was trimmed).

By 4:00 p.m. on 14 May, sales of the airmail stamps were stopped by postal officials. For the next two hours, clerks inspected the supply for additional error sheets. Sales resumed at 6:00 p.m.

Although Robey had never disclosed his name or address to any of the postal clerks, a co-worker at Hibbs revealed it that afternoon while searching for more errors at one of the branch post offices. According to Robey, on the day he bought the sheet he was visited at his office by two postal inspectors, who attempted to confiscate it. Their efforts were rebuffed by Robey, who stated that he had purchased the sheet for face value at the post office and had as much right to ownership as anyone who had ever purchased other stamp errors over the counter. Frustrated and indignant at Robey’s refusal to comply with their demands, the two inspectors left.

14-19 May 1918—Dealer to Dealer

Back to TopRobey was in his 20s when he bought the Inverted Jenny sheet. He and his wife of five years, Caroline, had an infant daughter and lived in a modest apartment. Although Hibbs and Company paid him a decent salary for his position as an auditing clerk, the prospect of making thousands of dollars on the resale of his Inverted Jenny sheet had life-changing implications. The day Robey bought the sheet, he began soliciting offers from the dealers he knew.

His first call was to Hamilton F. Colman, a Washington, D.C., dealer of some renown. Colman was not in the office when Robey called, and his assistant, Catherine L. Manning, listened incredulously as Robey described his new find. Manning went on to become the first woman outside the sciences to achieve the position of Assistant Curator at the Smithsonian and helped care for the national stamp collection for nearly 30 years, from 1922 to 1951. After learning about the discovery, Colman stopped by Robey’s office later in the day, examined the sheet, and made a token $500 offer for it, which was briskly rejected. After work, Robey met Colman at his office, where a small group had gathered, including Mrs. Manning. Among those present was Joseph B. Leavy, who had been a stamp dealer in New York City before the turn of the century and was, at the time of the meeting, the first “Government Philatelist” in charge of the national stamp collection. Leavy was intimately familiar with the USPOD and BEP operations, and he published frequent reports about new issues and production methods.

The first airmail issue was produced so quickly that Leavy never had time to learn about the production details in advance. Unaware that the stamps had been printed on the Spider Press from a plate of 100 subjects, Leavy observed the straight edges at the top and right of the Inverted Jenny sheet and assumed they were just like those on the quarter-section panes from sheets of 400. Leavy told the group that three other panes of 100 from a sheet of 400 had to be in circulation. Robey recollected this comment in his 1938 account, and it must have concerned him at the time.

Once Robey notified others about his discovery, dealers and collectors went on the hunt for more invert sheets. The two-hour stoppage of sales from 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. on 14 May meant that no one in the three cities where the stamps were available could buy them until postal clerks had time to check for errors. By the time sales resumed, the chances of finding an invert sheet were almost nil. The next day, 15 May, the BEP implemented the “Top” imprint strategy to prevent more errors from evading detection. If Robey had known that the small supply of 24¢ sheets in post offices had been thoroughly examined and that more errors were unlikely after the BEP changed the imprints, he might have been more confident that he possessed the only errors. However, most collectors were familiar with market decline that occurred after the 5c Red error (Scott 467 and 505) was discovered a year earlier. As more sheets containing the 5¢ error were found, the price dropped drastically. Leavy’s comment that 300 more Inverted Jenny stamps were waiting to be discovered must have given Robey a greater sense of urgency to sell while the selling was good.

The night of 14 May, Robey nervously walked the streets with his paper fortune in his briefcase. Concerned by the postal inspectors’ aggressive posturing, Robey’s employer refused to allow him to use the company safe to store the stamps overnight. When he finally returned home late in the evening, he and his wife fretted over keeping the stamps in their apartment.

On Wednesday, 15 May, the day of the first airmail flights, Robey mailed a letter to Elliott Perry, a prominent dealer who represented several major collectors in buying and selling. The letter was sent by regular mail early in the morning, and, in an era when a letter could actually travel from Washington, D.C., to Westfield, N.J., in one day, the mail carrier delivered Robey’s letter to Perry at 6:00 p.m. Later in the evening, after attending a dinner party, Perry called Robey and tried to secure the right of first refusal. Whether Robey actually agreed or not is uncertain, but Perry’s letter to Robey with a dollar silver certificate to confirm the agreement was promptly returned.

At the same time Robey reached out to Perry, he contacted Percy Mann, the Philadelphia dealer who used the “Special Aero Mail” labels found on early flight covers. Mann responded on Wednesday, 15 May, asking if he could meet with Robey and examine the sheet. After seeing the intact sheet, Mann offered $10,000, but Robey turned him down, explaining that he still wished to go to New York to obtain offers. Mann asked for the opportunity to bid higher if his offer was equaled or topped, and Robey agreed. On Friday afternoon, after a day’s work, Robey boarded the northbound train and arrived in New York around 9:00 p.m. He was greeted at the Hotel McAlpin by Percy Doane and Elliott Perry, who had arranged to meet Robey and examine the sheet. The two dealers asked Robey if he had received any offers, and Robey informed them that he had turned down $10,000. Robey went to sleep that night with a plan to find a buyer the next day.

On Saturday morning, 18 May, Robey walked down to 111 Broadway to pay a visit on Colonel Edward H. R. Green at the colonel’s office. The receptionist informed Robey that Colonel Green was away for a few days, so Robey left, not realizing that the person he had hoped to see would be the ultimate buyer in two days.

Robey’s next stop was the office of Stanley Gibbons Inc., the American company run by Eustace B. Power. After receiving a $250 offer and a warning from Power that he was negotiating for the purchase of three other sheets, Robey left to visit the office of Scott Stamp & Coin Company. He was told that they did not wish to make an offer, but would sell the sheet for a commission.

Feeling “rather low and disgusted” by his morning of failed efforts, Robey returned to his hotel to find one of the Klemanns of Nassau Stamp Company waiting for him. After examining the sheet, Klemann offered Robey $2,500. Upon hearing from Robey that someone had already offered four times that amount, Klemann lashed out, saying that Robey was crazy, and anyone offering $10,000 was also crazy, and off he went.

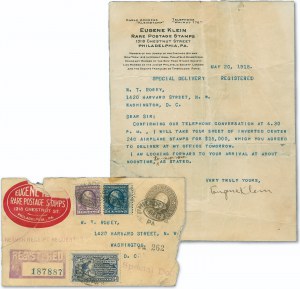

Robey called Mann on Saturday night to say that he had not received an equivalent or better offer while in New York, but had decided to keep the sheet rather than sell it for $10,000. Mann asked if Robey would stop in Philadelphia on the Sunday return trip, and Robey agreed to do so. At Philadelphia, Robey was met by Mann, and the two visited the home of Eugene Klein, one of the country’s leading dealers. Days earlier, on 14 May, Klein had prepared envelopes with the new 24¢ airmail stamp and addressed them to colleagues in the U.S. and overseas. They were carried on the 15 May inaugural flight from Philadelphia. The typewritten letter Klein inserted into each cover states that sales of the new airmail stamp started in Philadelphia on 14 May at 12:00 noon, but were stopped at 4:00 p.m.

19-21 May 1918—Sold!

Back to Top

The meeting between Eugene Klein and William T. Robey, with Percy Mann as matchmaker, was to have profound effects on the future of philately.

Klein was a seasoned negotiator. No doubt he had been informed by Mann that Robey had turned down a $10,000 offer, but also that no equivalent or higher offers had been made in New York. Klein asked Robey to set the price, and in response Robey said he would take no less than $15,000. After consulting with Mann, Klein asked Robey for an option at $15,000, which would expire at 3:00 p.m. the next day (Monday, 20 May). Robey agreed.

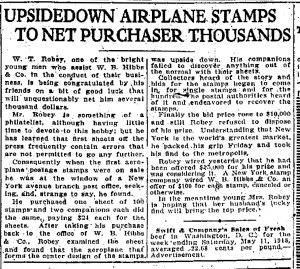

In a curious twist on the story told by Robey and repeated by others, the Washington Evening Star published an article on 19 May (shown at right), stating that they had received a wire from Robey “yesterday” (Saturday, 18 May), informing them that he had received an offer of $15,000 for the sheet and was “considering it.” Who made that offer, and when? Robey never mentioned another $15,000 offer, and the timing of the newspaper article and reference to a wire from the previous day make it impossible for that offer to be the one made by Klein on Sunday. Did Robey deliberately feed the newspaper misinformation on Saturday to generate higher offers?

If so, perhaps it worked. On Monday morning, Robey received a telephone call from H. F. Colman, the dealer who had offered $500 for the sheet six days earlier. He was now ready to pay $18,000! Colman was apparently inspired by something or someone to increase his offer by a multiple of 36. Robey could not accept the offer until Klein’s option expired later in the day. Whether it expired at 3:00 p.m., as Robey recollected, or 4:30 p.m., as indicated in Klein’s confirmation letter to Robey (shown at right), is unclear and not very important. By the end of 20 May, the sheet was sold to Klein for $15,000, subject to delivery and payment the following day.

Image: Don David Price

Robey and his father-in-law traveled to Philadelphia on Tuesday, 21 May, and delivered the sheet to Klein at noon. Robey was handed a certified check for $15,000, which gave him a $14,976 profit on his $24 post office purchase. One wonders what Robey and Caroline’s father discussed on the return trip home, with Klein’s $15,000 check in hand.

1918—The Colonel’s Inverts

Back to Top

Image: © The New York Times

The accounts of the sale from Robey to Klein and then to Colonel Green have conflicting details (the Amick book goes into depth on the differing accounts). One aspect of the transactions is definite: Colonel Green bought the sheet no later than Monday, 20 May, the day Klein exercised his option to buy it from Robey. On 21 May 1918, the New York Times morning newspaper ran a story announcing that Colonel Green purchased the sheet for $20,000 (shown at right). The newspaper must have been informed of the purchase on 20 May by someone other than Robey, who could not have known about the resale. It is remarkable that a news story about the $20,000 resale to Colonel Green was published Tuesday morning, before Robey reached Philadelphia to deliver the sheet and collect payment from Klein.

The price represented a $5,000 profit for Klein, who kept half and shared the rest with Percy Mann and Joseph A. Steinmetz, who had formed a “combine” with Klein for the negotiations.

Edward Howland Robinson Green (1868-1936) was the son of Hetty Green (1834-1916), one of the wealthiest and most astute investors in American history. Hetty’s extreme frugality was exploited by her adversaries and made for good copy in the press, but in reality she was a woman in a man’s world, during the era of robber barons and deals done in dark oak rooms with thick blue cigar smoke. Her reputation as the “Witch of Wall Street” was undeserved, and in fact she despised many of the titans of industry and finance for their predatory ways and profligate spending. She sympathized with the average hardworking citizen who had to pay more for basics, because of trusts and monopolies that fixed the costs of goods and services.

Hetty’s son “Ned” was obese and had a prosthetic leg, the result of a childhood injury that was improperly treated with homeopathic medicine. Nonetheless, he was a skilled manager of the family’s business affairs and earned Hetty’s trust, as opposed to her husband and Ned’s father, Edward Green, whose bad investments and excessive borrowing forced Hetty to bail him out when the bank foreclosed.

When Hetty died in 1916, she left an estate variously estimated to be worth $100 million to $200 million, the equivalent of $2 billion to $4 billion in 2016. Her two children, Ned and his sister Sylvia, shared the estate equally. One year later Ned was free to marry his long-time girlfriend, Mabel E. Harlow, whom Hetty had accepted as her son’s companion as long as he did not risk the family fortune by marrying her. Mabel, a voluptuous, red-headed stage performer from Texas, went along with the informal arrangement while Hetty was alive.

With his newly-inherited wealth and freedom from his mother’s disapproving view of conspicuous consumption, the 300-pound six-foot-four Colonel Green embarked on a buying spree of unbridled extravagance. By some estimates he spent more than $3 million on everything from stamps and coins to jewelry and erotic literature. At one point he owned all five 1913 Liberty Head nickels. Of course, on 20 May 1918 he became the new owner of the Inverted Jenny sheet through the deal arranged by Eugene Klein.

Colonel Green authorized Klein to divide the sheet into singles and blocks, and to sell what the colonel did not retain for his own collection. Before doing so, Klein lightly penciled the position number on the gum side of each stamp, enabling future philatelists to cite every stamp by its exact location in the sheet. Klein initially advertised fully perforated singles from the sheet for $250 and straight-edge positions (top or right) for $175. He then withdrew the offering, giving the disingenuous explanation that he had placed the sheet privately, and asked prospective buyers to apply for a price. As the facts show, the sheet had been sold to Green before Klein even took possession of it. Klein and Green discussed pricing and changed the prices over the next three months. As Klein reported, by the end of July most of the singles without straight edges had been sold for prices ranging from $250 to $325.

In the series of 28 auctions held from 1942 to 1946 to disperse Colonel Green’s stamp collection after his death in 1936, 38 different Inverted Jenny stamps were offered. Included in this total were the block of eight from the bottom with the plate number selvage, three blocks of four, five full perforated stamps and 13 of the original straight-edge stamps. The 18 extra singles were presumably unsold and returned by Klein to the colonel. Eight of the straight-edge copies were found after the colonel’s death, stuck together in an envelope; they were soaked apart and lost their gum before being offered in the Green sales.

Colonel Green was regarded as a somewhat careless custodian of his vast stamp collection. Some accounts report that he had his young female “wards” dismantle collections that had been meticulously written up by leading philatelic scholars. Another story about some Inverted Jenny stamps going down with his yacht is apocryphal. However, the colonel did, in fact, have a locket made for his wife Mabel, which contained Position 9 and, on the flip side, a normal 24¢ stamp (shown at left). The famous “Locket Copy” was left by Mabel to a female friend in 1950, and after the friend’s death it appeared for the first time in a Siegel auction in 2002.

While Klein was pulling apart the Inverted Jenny sheet, and Robey and his wife were making plans for what to do with their windfall, poor H. F. Colman—the dealer who raised his offer from $500 to $18,000—was trying to find more of the errors. Through an intermediary, Captain A. C. Townsend, he convinced Thomas G. Patten, the New York City postmaster who mailed a first flight cover and letter to President Wilson, to let Joseph Leavy search the supply of sheets contained in the post office vault. Packages of full sheets were opened and inspected, but the all of the planes were flying rightside up. One wonders what would have happened if Colman, Townsend and Leavy had actually found another sheet. Letting a few individuals profit from the special privilege of accessing the post office vault hardly seems like proper civil servant policy.

As for Robey, although he continued to enjoy stamp collecting for another 31 years, he never owned another Inverted Jenny after selling the sheet to Klein. He continued to report other philatelic “discoveries,” but none were even remotely comparable to the Inverted Jenny. After witnessing the complete dispersal of Colonel Green’s holding of Inverted Jenny stamps, Robey passed away in February 1949.

Back to Top