History

The World's First Government Airmail Service

Pre-1900 – U.S. Mail Carried by Balloons

1910-1916 – Pioneer Flight Mail

1910-1917 – Legislative Efforts to Fund Airmail

1918 – Congress Appropriates $100,000 for “Experimental Aeroplane Mail Service” and Establishes 24¢ Airmail Rate

May 1918 – First U.S. Airmail Route and Schedule

1918 – Airplanes Used for Aerial Mail Service

15 May-10 August 1918 – Airmail Carried by U.S. Army Aviators

14-15 May 1918 – Preparation for First Flights

15 May 1918 – Historic Flights and Failure

16-17 May 1918 – More Problems

15 May-15 June 1918 – Performance During First Month

The World's First Government Airmail Service

The world's first regularly scheduled mail service using airplanes was inaugurated in the United States on Wednesday, 15 May 1918.

The flights on this day marked the first attempt to fly civilian mail using winged aircraft on a regular schedule, which distinguishes this service from earlier official airmail carried on balloons or on airplanes used for short-term or restricted flights; for example, aviators carried souvenir letters at special flying events from 1910 to 1916, and the U.S. Army First Aero Squadron carried some mail by airplane between Mexico and New Mexico during the 1916 Punitive Expedition against “Pancho” Villa.

On Monday, 12 August 1918, after three months of experimental airmail service under U.S. Army supervision, the U.S. Post Office Department (USPOD) took control of the planes and pilots, and airmail service became a permanent civilian operation, the first of its kind. The last Army-operated airmail flight was on Saturday, 10 August 1918.

With its regular flight times, specific routes and public utility, the 1918 airmail service is regarded by historians as the starting point of commercial aviation.

Pre-1900 – U.S. Mail Carried by Balloons

Back to TopJupiter Flight – The earliest recorded U.S. official “airmail” flight took place in August 1859. The plan was to carry a mailbag from Lafayette, Ind., east to New York City (or as far as possible) on board the balloon Jupiter, piloted by famed balloonist, Professor John Wise.

The Lafayette postmaster, Thomas Wood, gave Wise a locked mailbag addressed to New York City. Wherever Wise happened to land, be was oath-bound as an official mail carrier to deliver the mailbag to the nearest post office. For this reason, the Jupiter flight is considered to be the first postal conveyance by air sanctioned by the USPOD.

On 17 August 1859, after a one-day delay due to a gas leak in the balloon, the Jupiter ascended with the mailbag containing 123 letters and 23 printed notices. Weak air currents forced Wise to descend after just five hours and seven minutes.

While aloft, Wise tossed the mailbag overboard with a makeshift parachute, then followed the descending mailbag to its final landing position near Crawfordsville, Ind. After disembarking, Wise carried the mailbag to a Col. Reed, the postal agent on the New Albany & Salem Railroad line, and it was transported east by train.

Although unsuccessful, the 1859 Jupiter flight is still regarded as the first time mail was carried by air with the involvement of a post office. A U.S. commemorative stamp was issued in 1959 to mark the 100th anniversary of the Jupiter flight.

One flown Jupiter cover with its original letter was discovered in 1957 and is displayed at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. (see http://postalmuseum.si.edu/collections/object-spotlight/balloon-jupiter.html).

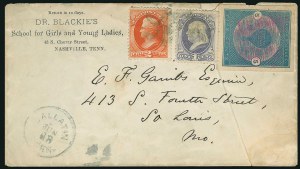

Buffalo Flight– The Buffalo was built for Samuel Archer King in 1873 and had a capacity of 91,000 cubic feet and seating for nearly twenty passengers. It made one of its celebrated ascents from the grounds of the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia on 4 August 1876.

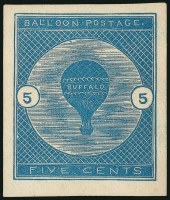

A Buffalo Balloon 5¢ stamp was prepared in time for the Nashville, Ten., flight in June 1877. The 5¢ stamps had no postal value, but they were sold for use on letters deposited at the U.S. Signal Service office in Nashville for conveyance on the Buffalo.

The Buffalo Balloon stamp was designed by John F. B. Lillard and engraved in wood by John H. Snively. A total of 300 stamps were printed in blue on gummed white paper by Wheeler Brothers Printers in Nashville. It has been stated that only 23 were used.

The 18 June 1877 ascent from Nashville took place at 5:00 p.m. On board with King were Dr. A. C. Ford of the U.S. Signal Service and five other passengers. The Buffalo reached 6,300 feet and landed at Gallatin, Ten., at 7:18 p.m., 26 miles from its starting point. The letters carried by King were left at the Gallatin post office.

The flight continued the next morning (19 June) at 8:00 a.m. and reached an altitude of 17,000 feet before descending and landing at Taylorsville, three miles away from Gallatin (source: The Balloon, 1879, The American Aeronautic Society of New York).

Image: Siegel Auction Galleries

Three covers with the Buffalo Balloon stamp are recorded. Two have Gallatin postmarks dated 18 June and are known positively to have been flown from Nashville. A third has no postal markings and is believed to have been carried on a different flight.

1910-1916 – Pioneer Flight Mail

Back to TopThe Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, achieved success with the first controllable, sustainable heavier-than-air flying machine at Kitty Hawk, N.C., on 17 December 1903.

After obtaining a patent on the wing-control mechanism and securing sale contracts with the U.S. and French governments, the Wrights made their first public demonstration flights in 1908.

Wilbur flew first in Europe, beginning on 8 August 1908, near Le Mans in France. Orville started his contract acceptance flights for U.S. military officials at Fort Myer, Va., on 3 September 1908.

On 17 September 1908, Orville and a passenger, Lieut. Thomas E. Selfridge, crashed after a propeller split and cut the control cables, causing the plane to plummet one hundred feet to the ground. Orville suffered severe fractures to his hip, legs and ribs, and Lieut. Selfridge died later that day, becoming the first fatality in a winged-aircraft accident.

After observing additional acceptance flights in July 1909, the U.S. Army completed its first purchase of an airplane, paying the Wrights $25,000 plus $5,000 for exceeding the speed requirements ($1,000 for each mile achieved over 40 mph).

At the 1909 Hudson-Fulton celebration in New York, Wilbur flew up the Hudson River and back in one of the first flights witnessed by the American public.

In 1910 the first legislative bill contemplating airmail service was submitted to Congress, but was never reported by the House committee.

In response to this legislative measure and with the encouragement of postal officials, pioneer aviators who conducted display flights at carnivals, fairs and other special events began carrying small quantities of mail as souvenirs. Mail from these flights is classified as official Pioneer Flight mail.

True Pioneer Flight mail has varying degrees of an official connection to the USPOD. At a minimum, the aviator received the approval and cooperation of the local postmaster to fly mail. Some Pioneer Flights were assigned official route numbers by the USPOD in Washington, D.C. A complete list of Pioneer Flights can be found in the American Air Mail Catalogue.

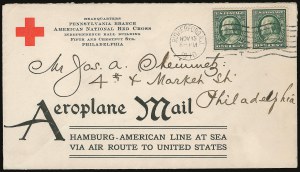

Earliest Pioneer Flight – The earliest Pioneer Flight was scheduled to take place on 3 November 1910 in an experiment to test the feasibility of launching an airplane from a platform connected to a ship. The plane would carry mail, small articles and valuable papers from ship to shore.

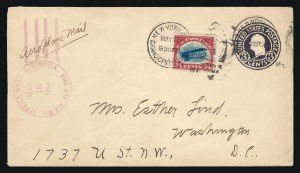

The 3 November flight was intended to launch from the Hamburg-American Line's Kaiserin Augusta Victoria when the ship was located about 50 miles at sea, opposite the south shore of Long Island.

Due to bad weather conditions, the 3 November flight from the Kaiserin Augusta Victoria was cancelled. Another flight was scheduled for 10 November from the S.S. Pennsylvania, but it, too, had to be cancelled when the plane's propeller broke shortly before takeoff.

Image: Siegel Auction Galleries

The mail from these aborted ship-to-shore flights was taken off the ships and deposited at post offices in New York City and Rutherford, N.J. Specially printed flight envelopes exist with ordinary postmarks, but they were never flown. Still, they are considered to be the first Pioneer Flight items.

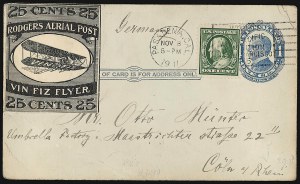

Vin Fiz Flight – The next major aviation event with postal significance was the Great Transcontinental Air Race. The contest was held by William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper publisher, who on 9 October 1910 offered a $50,000 prize to the first pilot to fly from Boston or New York to Los Angeles or San Francisco (or vice versa) in 30 days or less. The offer was good for one year, through 9 October 1911.

Four pilots entered the race – Calbraith Perry Rodgers, Jimmy Ward, Bob Fowler and Earle L. Ovington – but Rodgers was the only one to complete the trip. The others dropped out early in the race.

Rodgers flew a Wright Flyer Model EX with the words “Vin Fiz” painted on the bottom of the wings. Vin Fiz was the name of a popular grape soda beverage manufactured by Armour and Company of Chicago, the flight’s sponsor.

The USPOD was not directly involved with any of the Rodgers flights, although local postmasters apparently offered their cooperation. All of the special markings found on Vin Fiz mail and the 25¢ adhesive stamp sold by Rodgers and his entourage were unofficial. Rodgers collected letters along the way and flew them between stops or on daily exhibition flights.

Image: Siegel Auction Galleries

Rodgers did not meet the time deadline set by Hearst. After starting from Sheepshead Bay on Long Island, N.Y., on 17 September 1911, Rodgers had flown only as far as Marshall, Missouri, by 10 October, the day Hearst's offer expired.

Still, Rodgers persevered and completed the transcontinental journey. On 3 November 1911 he reached Imperial Junction, Cal., where the plane's engine exploded and Rodgers crash landed. He arrived at Pasadena on 5 November, which marked the completion of Rodgers' coast-to-coast flight. After a delay caused by a serious crash at Compton, Cal., Rodgers landed in Long Beach on 10 December 1911 and touched the Pacific Ocean with his plane as a symbol of achievement.

Rodgers died on 12 April 1912 when seagulls flew into his plane and caused him to crash during an exhibition flight at Long Beach.

First U.S. Airmail Carrier and Route – The first aviator to carry mail as a USPOD-appointed carrier was Earle L. Ovington. His first official flight took place on 23 September 1911, the opening day of an international aviation meet held on Long Island by the Nassau Aviation Corporation.

Image: Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Ovington carried 640 letters and 1,280 postcards on the 23 September first flight between Garden City and Mineola in a French-manufactured Bleriot “Dragonfly” monoplane. He continued to carry mail during the event, as weather permitted.

Following the aviation meet, which concluded on 1 October 1911, Ovington planned to fly mail across the country in the Hearst contest, although he obviously could never reach the West Coast by the deadline nine days away. This flight received the first official USPOD airmail route number (607,001).

The new airplane Ovington planned to fly across country suffered severe mechanical failure, and, after several attempts, the flight was cancelled on 11 October. There is only one recorded piece of mail that was clearly marked to be carried on this aborted flight.

The Pioneer Flight Period ended in the U.S. on 3 November 1916 when Victor Carlstrom completed a mail-carrying flight from Chicago to New York in a Curtiss R-7 biplane.

The numbers of recorded Pioneer Flights during each year from 1910 to 1916 are listed below.

1910-1917 – Legislative Efforts to Fund Airmail

Back to TopThe USPOD was funded each fiscal year (1 July–30 June) by a Post Office Appropriation Act of Congress. Each appropriation bill was named for the year in which its applicable fiscal period came to an end; for example, the Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1918 covered the fiscal period from 1 July 1917 through 30 June 1918.

There was a set procedure for the introduction, discussion, passage and signing of a Post Office Appropriation Bill. The bill would be introduced toward the end of the calendar year preceding the applicable fiscal year. It would then be referred to the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads. Following discussion within the committee, the bill would be reported to the floor for further discussion. A final vote would occur in the early months of the year that started the fiscal period, and, once approved, the president would sign the Act of Congress into law.

For example, the Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1918 was introduced at the end of 1916, reported in January 1917, put to a vote in February 1917, and signed into law in March 1917. The money appropriated by Congress covered the fiscal year starting 1 July 1917 and ending 30 June 1918.

Legislation concerning airmail service was first introduced in 1910, but without success. After several more attempts to obtain funding for airmail or to implement service, the Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1918 and a follow-up Act of Congress in 1918 (authorizing the 24¢ airmail rate) resulted in the first regular airmail service.

1910 Airmail Bill – On 14 June 1910 a bill [H.R. 26833] was submitted by Representative John Morris Sheppard (D-TX, later Senator) to the House of Representatives, authorizing the postmaster general “to investigate the practicability and cost of an aeroplane or airship mail between the City of Washington or some other suitable point or points for experiment... in order that it may be definitely determined whether aerial navigation may be utilized for the safe and rapid transmission of the mails.”

Senator Sheppard is often called “the father of airmail service,” but he is better known for his role in passing the Prohibition Act.

H.R. 26833 was referred to the House Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads, but the bill was not reported to Congress. In effect, the first legislative act contemplating airmail service died in committee. However, it inspired aviators to begin flying mail during exhibition flights, which postal officials encouraged as a means to test the process and arouse public interest in the concept.

1913 Appropriation – In November 1911, the same month Cal Rodgers reached California in the Vin Fiz, the Second Assistant Postmaster General, Joseph Stewart, asked Congress for an appropriation of $50,000 to start an experiment airmail service, to be included in the Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1913.

On 17 January 1912, Stewart appeared before the House Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads to persuade its members that airmail service would prove to be beneficial, particularly in regions where the topography made conventional mail transportation extremely difficult.

The Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1913 (H.R. 21279) was reported by the committee without the $50,000 appropriation, but on 20 April 1912 Representative William G. Sharp (D-Ohio) proposed an amendment to include $50,000 for the “transportation of mail by aeroplane or other air craft.” Sharp used the same arguments Stewart presented to the House committee to urge his colleagues to vote for the amendment.

Despite some support for the amendment to H.R. 21279, it was defeated in the House by a vote of 43 to 25, and the Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1913 was passed and signed without any funding for airmail service.

There were two principal arguments against the airmail amendment: first, that $75,000 had already been appropriated to the U.S. military for aviation experiments, thus it was wasteful to have two different government departments spending money on the same thing; and, second, that private enterprise should bear the costs of research and development in the aviation field.

1914 Appropriation – Undeterred by congressional refusal to fund airmail experiments, the USPOD continued to give its authority to Pioneer Flights (52 in 1912 alone).

Later in 1912 the USPOD issued a postage stamp with a design that arguably was intended to rally political support for airmail: the 20¢ Parcel Post stamp, which shows an image of a Wright-type airplane with the caption “Aeroplane Carrying Mail.”

In October 1912 postal officials requested the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) to create a set of twelve designs for the new Parcel Post stamps. The stamps' images were chosen to represent different mail services, modes of transportation, and American manufacturing and agricultural industries.

The design ultimately chosen for the 20¢ value was based on a photograph provided by postal officials, which showed an airplane “at rest.” The BEP was asked to add hills, trees and people to complete the picture of an airmail plane in flight, a vision which, in 1912, could only occur at Pioneer Flight events. Government airmail would not arrive for another five and a half years.

Considering the timing, circumstances and the design elements of the 20¢ Parcel Post stamp, the inescapable conclusion is that postal officials produced it to influence public opinion in favor of the development of airmail service.

At the end of 1912 and beginning of 1913, when the Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1914 was submitted to Congress (H.R. 27148), Stewart refrained from asking for another airmail appropriation, but Representative Sharp proposed an amendment to permit “the transportation of mail by aeroplane or other air craft” on routes in Alaska, where winter weather made mail conveyance on rivers impossible.

Sharp's amendment was killed by opponents on a point of order. In response, on 21 April 1913, Sharp introduced a separate bill [H.R. 3393], which authorized the postmaster general “to enter into contracts for carrying the mail by aeroplane or by any other similar device when in his opinion the efficiency, dispatch, or general interest of the service will be promoted...”

1915 Appropriation – H.R. 3393 languished in committee for seven months, but in December 1913 the new postmaster general, Albert S. Burleson, and Second Assistant Postmaster General Stewart provided their support. In addition to seeking general authorization, Burleson and Stewart gave Congress an estimate of $50,000 for an experimental airmail service in parts of the country where the topography favored air transport. The cost of such service would be incurred in fiscal year 1915.

The House committee reported H.R. 3393 on 10 December 1913. It was introduced as a measure to improve mail service in Alaska and certain western states, and to make the U.S. competitive with European countries where aviation was receiving much greater government support.

Once again, opponents in Congress fired shots at the bill, claiming that flying planes over mountains and in frigid temperatures was an untested and presumably impossible feat. Others complained that it would waste money and expose mail to great risk of damage or loss. Proponents argued that the naysayers knew nothing about aviation and that Congress should defer to postal officials.

The estimated expense, $50,000, was a trivial amount in the 1915 Post Office budget of $305 million, but congressional opponents to Sharp's bill spread fear that giving the postmaster general the authority to expand airmail service at his discretion would result in continuing and increasing appropriations well beyond $50,000.

Finally, opponents insinuated that airplane manufacturers were trying to line their pockets by influencing postal officials and House committee members to spend money on the equipment needed for airmail service.

In a vote of 54 to 28, H.R. 3393 was defeated in December 1913. The Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1915 (H.R. 11398), introduced on 12 January 1914, contained no reference to or funding for airmail service.

1916-1917 Appropriations – In their annual reports to Congress at the conclusion of the 1914 and 1915 fiscal years, postal officials continued to seek funding for an experimental airmail service, but they were rebuffed. In January 1916 another request from the USPOD for a $50,000 appropriation for experimental airmail service (for 1917) was rejected by the House Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads, but circumstances were changing, and the winds were shifting in favor of airmail.

One of the major factors that caused opponents to reconsider their position was World War I. As it became increasingly likely the U.S. would have to enter the war, preparedness dictated that the country should raise a large corps of military pilots. Flying the mail offered a practical means of training pilots to fly over different terrain and under a variety of weather conditions, while performing a valuable service.

In March 1915 the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was established to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. The NACA became an advocate of using airplanes to carry mail, which they believed would advance aeronautics in general.

On 12 February 1916 Senator John Morris Sheppard (D-Tex.) introduced a bill (S. 4417), appropriating $50,000 “to enable the postmaster general to establish an experimental aerial mail service, by aeroplane or other devices...” It was referred to the Senate Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads, but was not reported to the Senate.

Despite the House's refusal to appropriate any funds for airmail service, the Senate committee reviewing the Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1917 (H.R. 10484) recommended adding “aeroplanes” to the modes of transportation covered by the $1,060,000 appropriation for inland transportation routes. The Senate voted in favor of this amended bill without any discussion, and the House followed in July 1916, making H.R. 10484 the first legislative act to authorize the use of airplanes to carry mail.

Despite this legislative success, H.R. 10484 did not produce any tangible results. Months before its passage, the USPOD had already taken a major first step toward a limited form of airmail service. On 12 February 1916 an official USPOD advertisement solicited bids from private contractors for carrying mail by airplanes on eight routes – one between Nantucket and New Bedford, Mass., and the other seven in Alaska.

Postmaster General Burleson had no authority from Congress to initiate an airmail service until the passage of H.R. 10484 and the start of the new fiscal year on 1 July 1916, so his bold move in soliciting bids in February must have been predicated on the likelihood of receiving congressional approval. On the day the advertisement was published, Senator Sheppard introduced his bill appropriating $50,000 for experimental airmail service (S. 4417), so perhaps the senator and postal officials coordinated a two-pronged effort to break the bureaucratic deadlock.

The logistical problems involved in carrying mail, especially on the remote routes in Alaska, deterred private contractors from submitting bids in response to the February 1916 solicitation. When the time to submit bids expired on 12 May 1916, only one contractor had responded, and even that proposal failed to provide the required bond.

1918 – Congress Appropriates $100,000 for “Experimental Aeroplane Mail Service” and Establishes 24¢ Airmail Rate

Back to TopAs the year 1916 came to an end, Postmaster General Burleson and his new Second Assistant Postmaster General, Otto Praeger, renewed their request to Congress for an appropriation for 1918, raising it to $100,000 and including the use of dirigibles in the experiments.

The Post Office Appropriation Bill for 1918 (H.R. 19410), reported by the House Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads on 2 January 1917, contained the following authorization for airmail service:

“For inland transportation by steamboat or other power-boat or by aeroplanes, $1,224,000; Provided, That out of this appropriation the Postmaster General is authorized to expend not exceeding $100,000 for the purchase, operation, and maintenance of aeroplanes for an experimental aeroplane mail service between such points as he may determine.”

When H.R. 19410 was discussed in the House, opponents voiced concerns over Postmaster General Burleson's earlier suggestion that dirigibles might be used to carry mail. The objection resulted in the entire airmail appropriation being deleted by the House, but the Senate committee restored the original language and reported the bill to the Senate for discussion on 9 February 1917.

H.R. 19410 with the airmail service provision was eventually passed by the House and Senate, and it was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on 3 March 1917. One month later the U.S. entered the war against Germany.

In February 1918 Postmaster General Burleson solicited bids for building five airplanes to be used in a “permanent” airmail service, and the route suggested was between Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and New York City. The service was to commence on 15 April 1918.

The 1918 appropriation specifically authorized the USPOD to purchase, operate and maintain equipment for airmail service, rather than enter into contracts with private operators. Congress and postal officials had decided it would be better to own the operation, instead of outsourcing it, perhaps as a result of the poor results of the previous year's efforts to obtain bids from the private sector. As it turned out, the USPOD turned to the U.S. Army for planes, pilots and assistance.

On 1 March 1918 Second Assistant Postmaster General Praeger reached an agreement with the U.S. Army Signal Corps to use Army pilots and planes for the first year. This arrangement was deemed mutually beneficial. The USPOD would have immediate access to experienced pilots and planes, and the daily flights would provide Army pilots with additional training and experience. The commencement date was moved to 15 May 1918.

On 3 May 1918 the Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, passed along executive orders to organize the airmail service to Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, who was then a colonel and assistant director of the Division of Military Aeronautics, just as it was separating from the Signal Corps. The responsibility to equip and man the airmail service was given to Maj. Reuben H. Fleet, chief of U.S. Army pilot training, and Col. Edward A. Deeds and Capt. Benjamin B. Lipsner, both assigned to Air Service Production.

With the arrangements and start-up date in place, Postmaster General Burleson realized that he did not have authority to establish a special airmail postage rate, a power reserved for Congress. On 28 March 1918 Senator Sheppard introduced a bill [S. 4208] authorizing the postmaster general to charge 24¢ per ounce for mail carried by airplane.

When S. 4208 was introduced to the Senate on 6 May 1918 and debated on the floor, a few senators expressed lingering doubts about the feasibility or demand for airmail. One senator predicted that airmail would be a “two-days' wonder, not a seven-days' wonder.” Nevertheless, the bill passed and was signed by President Wilson on 10 May 1918, just five days before the first flights were set to take off from Washington, D.C., and New York City.

Engravers at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing had already started working on the new 24¢ airmail die, days before the legislative act authorizing the stamp had been passed. There was no time to waste on formalities.

May 1918 – First U.S. Airmail Route and Schedule

Back to TopThe first regular airmail route between Washington and New York was measured at a distance of approximately 225 miles, with an intermediate stop at Philadelphia. The reported distances varied, but the USPOD official reports calculated the Washington-Philadelphia leg at 135 miles and the Philadelphia-New York leg at 90 miles.

Four intermediate emergency landing locations were established at Baltimore and Havre de Grace, Md., Wilmington, Del., and New Brunswick, N.J.

Postal officials and Maj. Reuben H. Fleet, the U.S. Army officer in charge of the actual flight logistics, selected airfields near each of the three principal cities.

Washington, D.C. – For the airfield in Washington, D.C., postal officials chose the Potomac Park Polo Field, a grassy area between the Tidal Basin and the Potomac River, near the Lincoln Memorial. The Polo Field's proximity to the main post office suited postal officials. However, the field was small and surrounded by trees, making it problematic for takeoffs and landings. Maj. Fleet objected and recommended using the Army airfield at College Park, Md., but he was overruled by postal officials.

Before the first flight from the Potomac Park Polo Field, Maj. Fleet requested park authorities to cut down an obstructive tree. When he was told it would take weeks or months to obtain approval for tree removal, he ordered his men to cut it down. When protests reached up the chain of command and Maj. Fleet was confronted over his decision, he said he did what he had to and did not care about procedure. Satisfied with that answer, his superior let the matter drop.

New York – At the New York end of the route, Maj. August Belmont Jr. offered the government use of the open field at Belmont Park Race Track on Long Island. Belmont, at the age of 64, had received a commission as quartermaster in the American Expeditionary Force. Since the airmail service was a military operation, not civilian, he felt duty-bound to make his race track a free contribution to the war effort.

Concerned about his age and duties abroad, Maj. Belmont had also auctioned off a large number of his prized yearlings, including one he had held in high regard – a handsome red thoroughbred his wife had named to reflect the times, the legendary Man o’ War.

Belmont Race Track was far from the New York City main post office, but trucks and a special Long Island Railroad train link to Pennsylvania Station would be used to shuttle the mail back and forth.

Philadelphia – Bustleton Field, located near the railroad station in a suburb of Philadelphia, about fifteen miles northeast of Center City, was chosen as the intermediate airfield where the relay flights would operate between Washington and New York. Surrounding telephone and telegraph wires presented dangerous obstacles, but the 130 acres of flat open field were ideal for takeoffs and landings.

Schedule – Flights were scheduled to run six days a week, Monday through Saturday, leaving simultaneously at 11:30 a.m. from Washington and New York. The announced flight time from start to finish, including a few minutes to transfer the mail between planes at Philadelphia, was three hours.

The scheduled flying time was one hour and fifty minutes between Washington and Philadelphia (128-135 miles) and one hour between Philadelphia and New York (85-90 miles).

According to the plan, the northbound plane would depart from Washington-Potomoc Park at 11:30 a.m. and arrive at Philadelphia-Bustleton at 1:20 p.m. The northbound “through” mail to New York would be transferred to the relay plane, while mail addressed to Philadelphia and other places served by that city's distribution office would be carried by truck to the post office. The plane from Philadelphia was expected to reach New York by 2:30 p.m.

Simultaneously, the southbound plane would depart from New York-Belmont at 11:30 a.m. and arrive at Philadelphia-Bustleton at 12:30 p.m. The southbound “through” mail to Washington would be transferred to the relay plane, and the Philadelphia mail would be trucked to the post office. The plane from Philadelphia was expected to reach Washington by 2:30 p.m.

The airmail arrival times were coordinated with train departures from the main post offices, so that letters sent by airmail would be hours ahead of the regular mail.

The flight times reliably reported on the first day were 1hr22m for the northbound Philadelphia-to-New York flight (Lt. Culver’s report) and 1h36m for the southbound Philadelphia-to-Washington flight (Lieut. Edgerton’s report).

The speed for the period from 15 May to 31 December 1918 averaged 72 mph (depending on which flight statistics are used), which is about 3h3m flying time plus six to nine minutes (as reported) mailbag transfer time at Philadelphia. Therefore, the actual overall flying performance in 1918 averaged only slightly longer than anticipated.

1918 – Airplanes Used for Aerial Mail Service

Back to TopOn 1 March 1918 the Army placed an order with the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company for 12 new airplanes to be used for airmail service. The order was divided equally between the Curtiss JN-4HM and R-4LM models. The “M” in each instance indicates the basic plane was modified to carry mail. An additional six JR-1B planes were ordered from the Standard Aircraft Corporation in July 1918 for use in the airmail service (the “B” model was a modified version of the Standard JR-1 training plane). The JR-1B’s were delivered on 6 August 1918.

Image: Smithsonian National Postal Museum, Benjamin Lipsner Collection

Only the JN-4HM planes were used for the first airmail flights. The model that appears on the 24¢ stamp is an unmodified trainer with two seats. The photograph provided by the War Department to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was made from one of the regular Jennys, not a modified mail plane.

Curtiss “Jenny” – In 1915 Curtiss began production of a new plane that combined features of the earlier “J” and “N” models used by the Army and Navy. The JN series' initials gave rise to the plane's popular nickname “Jenny.”

The JN models began with limited production of the JN-1 and JN-2. After two fatal accidents involving the JN-2, the JN-3 was developed to correct the JN-2's shortcomings and used during the U.S. Army’s Punitive Expedition against “Pancho” Villa in Mexico in 1916.

The further improved JN-4 model was widely used to train military pilots. The “H” in the JN-4H indicated the plane was equipped with an 8-cylinder, 150-horsepower Hispano-Suiza motor, which was more powerful and reliable than the OX-5 motor used in the standard JN-4. The “Hisso” engine gave a Jenny enough power to fly 93 mph at sea level and climb to nearly 13,000 feet.

The Jenny's frame was made of spruce and covered with a fabric that was doped with a waterproofing material. At approximately 43 feet, the upper wing of the biplane was wider than the lower, and the length from propeller to tail was approximately 27 feet. The narrow width of the Jenny's landing wheels had caused planes to tilt and hit the ground during landing. To fix this problem, wing skids were added to maintain balance and prevent breakage.

The JN-4HT training model had twin seats and dual controls for the student in front and instructor behind. The six special-order JN-4HM planes – a modified version of the JN-4HT – were produced exclusively for the airmail service.

The JN-4HM planes had the forward pilot’s seat and control mechanism removed and replaced with a covered compartment, in which the mail could be placed. The Army's request for double fuel and oil capacity was met by simply attaching and linking extra 19-gallon gasoline and 2.5-gallon oil tanks.

In early 1919 Second Assistant Postmaster General Praeger published a comprehensive report (printed in Aerial Age magazine), listing the 18 planes that flew mail for the period from 15 May to 31 December 1918, each identified by serial number, flight data and cost of operation.

Praeger listed six each of the JN-4HM (with Hispano-Suiza 150hp motor, numbers 37944, 38262, 38274, 38275, 38276 and 38278), R-4LM (with Liberty motor, numbers 39362-39367) and Standard JR-1B (with Hispano-Suiza 150hp motor, numbers 1-6).

The six Curtiss Jenny airplanes used to fly mail are identified by serial number below with the flight miles and hours from Praeger's report.

Number 38276, with its relatively low mileage and hours of operation, could be the plane that Lieut. Stephen Bonsal, Jr., crashed at Bridgeton, N.J., on the second day, 16 May 1918, when he flew south from New York to Philadelphia.

Number 37944 has extremely low mileage and does not appear in Praeger's July 1918 report of monthly operations. These facts, the out-of-sequence number and reports of a two-seated trainer being used during the first few days’ flights suggest that this was not a fully-modified mail plane.

15 May-10 August 1918 – Airmail Carried by U.S. Army Aviators

Back to TopThe pilots and planes used for the government airmail service during its first three months were provided and controlled by the U.S. Army, which operated its aviation division under a series of different names throughout this period.

The Aeronautical Division of the U.S. Signal Corps was created in August 1907 to operate lighter-than-air dirigibles and winged aircraft. Its name and command remained the same from 1 August 1907 to 18 July 1914. It was reconstituted as the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps (18 July 1914 - 20 May 1918), then as the Division of Military Aeronautics (20 May - 24 May 1918). It was again reconstituted as the United States Army Air Service (USAAS – 24 May 1918 - 2 July 1926).

After the Saturday flight on 10 August 1918, responsibility for operating the airmail service was assumed by the USPOD. The first flight under civilian control was on Monday, 12 August 1918.

Major Reuben H. Fleet (1887-1975), chief of the U.S. Army flight training program, was chosen to be the officer in charge of the airmail service during the period of Army supervision. Maj. Fleet was a skilled and experienced pilot, and he was directly responsible for supervising the pilots and maintaining the equipment used in the airmail service.

After receiving the Distinguished Service Medal, Maj. Fleet resigned his commission in 1922 and went on to become a successful businessman in the aviation industry. In 1961 Maj. Fleet founded the San Diego Aerospace Museum. In 1973 the Fleet family helped establish the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center in San Diego. Maj. Fleet died on October 29, 1975.

Captain Benjamin B. Lipsner (1887-1971) was born in Chicago in 1887. He was not a pilot, but served as a U.S. Army officer in charge of the Lubrication Division of the Aeronautics section. Capt. Lipsner was deeply involved in organizing and supervising the airmail service from the beginning. Maj. Fleet was the ranking officer, but Capt. Lipsner apparently had more logistical responsibility assigned to him by the USPOD.

Capt. Lipsner later claimed that he was the “first” superintendent of the Aerial Mail Service. It is true that on 2 July 1918 Second Assistant Postmaster General Praeger sent a letter to Lipsner, appointing him Superintendent of the Aerial Mail Service, effective 1 August 1918, subject to the Army accepting Lipsner's resignation (http://postalmuseum.si.edu/collections/object-spotlight/lipsner-letter.html). As Superintendent, Lipsner clashed with Praeger over procurement and operation issues, and he resigned on 6 December 1918.

Capt. Lipsner died in 1971, and in 1982 his personal collection of correspondence and philatelic material from his airmail service was donated to the Smithsonian. It is now located in the Smithsonian National Postal Museum.

U.S. Army Pilots' Biographies:

Four of the six pilots originally chosen for duty in the airmail service were selected with the approval of Maj. Fleet (Lieutenants Bonsal, Culver, Miller and Webb). The other two, Lieutenants Boyle and Edgerton, were chosen by postal officials and had relatively little flying experience. Lieut. Boyle made two flights that resulted in crashes, and he was replaced with a more experienced pilot, Lieut. Kilgore.

Second Lieutenant Stephen Bonsal, Jr. (1893-1950) – Born in Madrid, Spain, on 3 June 1893, to Stephen and Daisy Bonsal. His father was a well-known Washington, D.C., news correspondent. Lieut. Bonsal, a Yale University graduate, served in World War I and World War II. He flew missions in Algeria, Tunisia and Italy with the Royal Air Force and with the 1st and 15th U.S. Air Force. He retired as a major in 1944 and died in 1950. (Source: Yale University Obituary Record).

Lieut. Bonsal was one of the four U.S. Army pilots originally chosen by Maj. Fleet for the airmail service. He has the distinction of being the second airmail pilot to crash. On 16 May 1918, flying south from New York to Philadelphia, he crashed at the Bridgeton Fairgrounds Race Track in New Jersey.

Second Lieutenant George Leroy Boyle (birth and death dates unknown) – At the time Lieut. Boyle was recommended by postal officials to be part of the airmail pilots team, he was engaged to Margaret McChord, daughter of the Hon. Charles C. McChord, a judge and chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission. Judge McChord’s position made him a valued ally of the USPOD during the legal battles over the government’s Parcel Post service initiative in 1913.

Lieut. Boyle was an inexperienced pilot, with approximately 60 hours of student pilot time. The USPOD’s insistence that he fly in the airmail service was viewed by some as a political favor to Judge McChord.

After two crashes on 15 and 17 May 1918, Lieut. Boyle was relieved of duty in the airmail service. He married Margaret on 15 June 1918. After the war Boyle worked as an attorney in Washington, D.C. The couple had children, but later separated. He is reported to have died in 1935. (Source: Amick, JENNY!).

First Lieutenant Howard Paul Culver (1893-1964) – H. Paul Culver was born in Eau Claire, Wis., in 1893. He received a degree in mechanical engineering from the Illinois Institute of Technology. Lieut. Culver learned to fly at the Curtiss School of Aviation in Newport News, Va., and received his pilot’s certificate on 25 August 1916. During World War I, he was a test pilot and instructor in combat flying at several U. S. Army airfields. He was one of the four U.S. Army pilots originally chosen by Maj. Fleet for the airmail service. Lieut. Culver died in 1964. (Source: Early Birds of Aviation, CHIRP, December 1964).

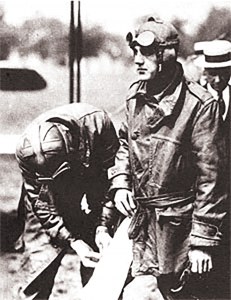

Second Lieutenant James C. Edgerton (1896-1973) – Lieut. Edgerton, another inexperienced pilot who was picked by postal officials because his father was the USPOD’s purchasing agent, was the first pilot to fly airmail to Washington, D.C., on 15 May 1918. Despite his inexperience, Lieut. Edgerton proved to be an outstanding aviator throughout his service.

When the USPOD took over the airmail service in August 1918, Lieut. Edgerton continued as a civilian airmail pilot and eventually became superintendent of flight operations. He later supervised installation of the first aeronautical radio stations and became superintendent of the USPOD radio service. He rose to the rank of colonel and served in World War II. After Colonel Edgerton died on 26 October 1973, the New York Times published an obituary under the headline “James Edgerton, Airmail Pioneer” (30 October 1973).

Image: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (ID: A19320001000)

The Abercrombie & Fitch leather coat Lieut. Edgerton wore on his historic 15 May flight is on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Second Lieutenant Edward W. Kilgore (birth and death dates unknown) – Lieut. Kilgore, U.S. Army, later captain, replaced Lieut. George L. Boyle in the Aerial Mail Service shortly after Boyle's second crash on 17 May 1918. Lieut. Kilgore flew Army exhibition flights.

First Lieutenant Walter Miller – Walter Miller was one of the four U.S. Army pilots originally chosen by Maj. Fleet for the airmail service. He left the airmail service in August 1918, and very little is known about his life. Lieut. Walter Miller should not be confused with Max Miller, who joined in 1919 and played an important role in the development of the first New York-to-Chicago airmail route before dying in a plane crash in 1920.

First Lieutenant Torrey H. Webb (1892-1975) – A graduate of Columbia University with a degree in mining engineering, Lieut. Webb was one of four U.S. Army pilots originally chosen by Maj. Fleet for the airmail service. He became the first pilot to complete a leg of the first airmail flights on 15 May 1918, when he arrived in Philadelphia after flying from Belmont Field in New York. Lieut. Webb continued his airmail pilot service and flew the first New York-to-Boston airmail route on 6 June 1918. He later became a vice president of Texaco and lived in Corona del Mar, Cal.

A letter from Postmaster General Burleson to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, published in the September 1918 issue of Flying magazine, provides reliable information about the pilots, flights and volume of airmail carried from 15 May to 10 August 1918 (this Saturday was the last flight under Army control). An excerpt from this letter follows.

Excerpt from Postmaster General Burleson's letter to Secretary of War Baker, summarizing 15 May-10 August 1918 airmail pilots and flight statistics:

“...Lieutenant J. C. Edgerton made 52 trips on the mail route, with but a single forced landing, due to an accident to a magneto in his plane. His total flying hours were 106, and 36 minutes; and his total mileage was 7,155 miles.

“Lieutenant E. W. Kilgore made 39 trips on the mail route, with five forced landings; 85 hours and 50 minutes total flying time, with a total mileage of 5,670 miles.

“Lieutenant Walter Miller made 48 trips on the mail route, with four forced landings; 60 hours and 50 minutes total flying time, with a total mileage of 4,975 miles.

“Lieutenant Stephen Bonsal made 38 trips on the mail route, with four forced landings; 74 hours and 33 minutes total flying time, with a total mileage of 4,975 miles.

“Lieutenant T. H. Webb made 41 trips on the mail route, with but one forced landing; 44 hours and 49 minutes total flying time, with a total mileage of 3,680 miles.

“Lieutenant H. P. Culver made 36 trips on the mail route, with but one forced landing; 47 hours and 52 minutes total flying time, with a total mileage of 3,645 miles.

“I think it is a high tribute to the Army's training planes and their engines, as well as to the Mechanical Maintenance Department, that out of 270 flights conducted by the Air Section in carrying the United States mail, covering a grand total of 421 hours of flying, there were recorded but 16 forced landings.

“From May 15th to August 12th, the period during which the flying operations were conducted by the military authorities, a total of 20¼ tons of letter mail was dispatched between New York and Washington, at a saving of time of from 2 to 2½ hours daily.”

Burleson’s count of 270 flights combines the 254 uninterrupted flights and the 16 that resulted in forced landings. The information provided by Burleson is summarized in the following table.

Landings

Hours

MPH

Landings

Burleson’s letter omits the name and flight information for Lieut. George Boyle, who flew the first mail from Washington, D.C., on 15 May, which resulted in a forced landing south of Washington. Lieut. Boyle made another attempt on Friday, 17 May, which also resulted in a forced landing near Philadelphia. Shortly after, he was relieved of duty in the airmail service and replaced with Lieut. Kilgore.

14-15 May 1918 – Preparation for First Flights

Back to TopOn 30 April 1918 Maj. Fleet reported that the planes ordered from Curtiss had been built and would be shipped to the U.S. Army's Hazelhurst aviation field near Mineola. A memorandum dated 8 May from R. M. Jones of the Equipment Division reported that the planes would be shipped on Sunday, 12 May 1918.

Eight days lapsed between Maj. Fleet's report that the planes were built and Jones' report that they would be shipped on 12 May. Curtiss manufactured planes at its Garden City plant, very close to Hazelhurst, and the arrival of the six unassembled planes in crates on Monday, 13 May, indicates the planes were shipped from a short distance away. However, whether they were built from scratch at Garden City, or built somewhere else and finished there, is less certain from the available information.

It is assumed that the six planes shipped from the Curtiss plant were modified JN-4H models, but there is a possibility that one plane – number 37944 – was not fully modified. There are reports that a two-seat “trainer” plane was flown during the first few days. Jenny 37944 is identified on Lieut. Culver’s Pilot’s Daily Report for the Philadelphia-to-New York flight on 15 May, so it is certain that this plane was used to carry mail. However, the total mileage and flying time reported by Second Assistant Postmaster General Praeger in 1919 for number 37944 was only 550 miles and 7h19m (it was omitted entirely from his July 1918 monthly operations report).

The six unassembled Jennys in crates were numbered 37944, 38262, 38274, 38275, 38276 and 38278. The 8 May Jones memorandum date coincides with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing engravers’ work on the 24¢ airmail stamp die. Thursday, 9 May, is probably the day that the serial numbers were reported to the BEP, so that a number could be engraved on the plane pictured on the stamp. Coincidentally, the number used – 38262 – is the number of the first plane to fly from Washington, D.C. (More information about the engraving process will be found in the Production section.)

Maj. Fleet and five of the pilots under his command – Bonsal, Culver, Edgerton, Miller and Webb (Kilgore was not yet assigned to airmail service duty) – traveled by train from Washington, D.C., to Hazelhurst aviation field to assist in assembling and preparing the planes for the inaugural flight to take place in just two days. Lieut. Boyle remained in Washington, D.C., from which point he was expected to fly the first northbound mail on Wednesday morning.

As the officers and mechanics unpacked and assembled the planes on Monday, Maj. Fleet's crew discovered several serious mechanical problems that required fixing. They worked through the night, and, by late Tuesday afternoon, 14 May, two of the Jennys were ready to be flown to the Philadelphia and Washington airfields.

In his logbook for 14 May, Lieut. Edgerton recorded the following (excerpt with technical flying notes omitted):

From Lieut. Edgerton's logbook it is possible to confirm that he flew Jenny 38274 from the Hazelhurst Field (Mineola) to Belmont, then from there to Bustleton Field in Philadelphia.

Accounts of this 14 May late afternoon flight of the three Jennys state that Lieut. Culver flew a second mail plane (38262) and Maj. Fleet flew an unmodified Jenny training plane without extra fuel capacity. It is likely that Maj. Fleet piloted number 37944, because that plane was flown by Lieut. Culver from Philadelphia to New York on 15 May.

On this 14 May southbound flight, Maj. Fleet was forced to land twice in fields between New York and Philadelphia, in order to refuel with whatever small amount of gasoline he could locate. The report that this Jenny ran out of fuel between New York and Philadelphia indicates that the plane was not equipped with the extra gas tank.

When Maj. Fleet made his second landing, on a golf course a short distance from Bustleton (presumably at the Philadelphia Country Club), the wheel was damaged and he was unable to take off. Maj. Fleet found a ride to Bustleton and told his men to head to the golf course with gasoline and a replacement wheel.

Lieut. Culver either went alone or with Lieut. Edgerton; there are conflicting accounts. After fixing the wheel, Lieut. Culver piloted the Jenny back to Bustleton in the dark, possibly with Lieut. Edgerton, if there was a second seat still installed. By the time Lieut. Culver approached the landing field, it was dark. Earlier, people at the field had used their automobile headlights to light up the field, but by the time Lieut. Culver arrived, they were gone. Unable to see clearly, Lieut. Culver landed in a neighboring field with freshly-tilled soil, which caused the propeller to hit the ground and break.

As Tuesday turned into Wednesday, 15 May, the day of the inaugural airmail flights, the pilots and Maj. Fleet worked furiously to fix the damaged plane and ready the Jennys for their historic mission. At 8:40 a.m., number 38262 – the plane made famous by the stamp – was ready to fly. Maj. Fleet assumed the task of flying it to Potomac Park Polo Field in Washington, while Lieutenants Edgerton and Culver remained at Bustleton with 38274 and 37944, awaiting their turns to fly the northbound and southbound relays.

Lieut. Edgerton would fly 38274 to Washington with the Philadelphia southbound mail and the “through” mail that arrived from New York. Lieut. Culver planned to fly 38262 to New York after it arrived from Washington with the northbound “through” mail, to which he would add the Philadelphia northbound mail.

As Lieutenants Culver, Edgerton and the crew at Bustleton watched Maj. Fleet fly Jenny 38262 in a southwesterly direction toward Washington, they must have felt a mix of excitement and apprehension. The past 48 hours had been stressful. Mechanical problems and time pressures had conspired to potentially delay or disrupt the first flights. Now, with Maj. Fleet on his way to the nation’s capital, the two pilots had a few hours to make final inspections of the planes, perhaps drink some coffee and rest, and, of course, pray that nothing else would interfere with their mission. If any prayers were made, they were ignored.

15 May 1918 – Historic Flights and Failure

Back to TopAs the commencement date had approached, there had been great anticipation of the new airmail service among government officials and the public. Newspapers ran stories. People who received admission tickets to the airfields cleared their schedules. Stamp collectors put money aside to buy the new 24¢ airmail stamp when it went on sale on 14 May, in time to be used on First Trip mail.

By May 1918, only a decade had passed since the Wrights had revealed the capability of their flying machine in public display flights. During those ten years, amateur aviators had flown planes in many places throughout the world. Nations' armies were using planes to great effect in World War I. Aeronautic societies and the government's new aviation commission were advocating and analyzing the use of airplanes in all aspects of civilian and military life.

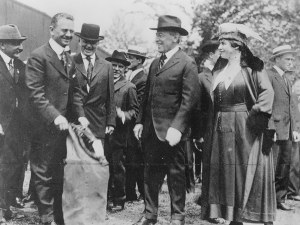

Now, after years spent pleading for money to create an airmail service, postal officials gathered with others on the Potomac Park Polo Field. In attendance were the postmaster general and his subordinates, legislators who supported the concept, dignitaries who wished to witness the spectacle, and even the President and First Lady. All of them, together with curious spectators, eagerly awaited the opening ceremony and hand-waving when the first plane departed north with the country's first airmail bags.

Attempted Northbound Flight from Washington (15 May) – A crowd of hundreds had already gathered at Potomac Park when the sound of the Jenny piloted by Maj. Fleet could be heard approaching in the distant sky. At 10:35 a.m., nearly two hours after taking off from Bustleton, Maj. Fleet landed 38262 on the Polo Field as spectators watched.

The northbound flight was scheduled for 11:30 a.m. Mail was accepted for the flight up to 10:30 or 11:00 a.m. and postmarked with a special “First Trip” marking. A mail truck marked “United States Air Mail Service” carried the mailbags to the airfield.

In attendance were President Wilson and his wife, Edith, who arrived by car shortly after 10:00 a.m. to greet honored guests, postal officials and the pilot, Lieut. Boyle. The President's left hand was bandaged; he had recently burned it on a tank's hot gun barrel while posing for photographs during a military display at Fort Rucker, Va.

Also present were Postmaster General Burleson, Second Assistant Postmaster General Praeger, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, Senator Sheppard (who introduced the Senate bills authorizing airmail service), and a youthful Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was then Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Roosevelt was standing firmly on his legs, three years before paralysis would strike. The future president, an avid stamp collector, must have been fascinated by the philatelic aspects of the day’s events.

Image: Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Among other dignitaries was a Japanese government official erroneously described as the “Postmaster-General of Japan” in news reports and subsequent accounts. In fact, the gentleman was KAMBARA Kushiro, Chief of the Planning Section of the Communications Bureau, a sub-division of the Communications Ministry (source: Japanese Philately, Vol. 12, No. 7).

President Wilson and postal officials posed for still and motion cameras. The archived video footage of the ceremony and takeoff can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhzmNvKY-i4

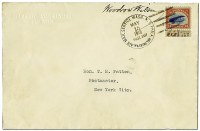

With the crowd watching and the camera rolling, President Wilson presented an autographed first flight envelope bearing one of the new 24¢ stamps with its selvage attached, on which six postal officials had signed their initials. The unique signed presidential envelope was addressed to New York Postmaster Thomas G. Patten (whose middle initial was misspelled “H” on the envelope). It contained a letter from Postmaster General Burleson.

This presidential First Trip souvenir was the brainchild of Noah W. Taussig, president of the American Molasses Company and a stamp collector, who pledged to place a starting bid of $1,000 on the envelope when it was put up for auction to benefit the Red Cross. On 11 June 1918, at The Collectors Club of New York, the auction conducted by J. C. Morgenthau failed to produce another bid.

Image: Smithsonian National Postal Museum

The envelope was later rediscovered among the Taussig family's possessions and, in 1977, Richard S. Taussig donated it to the National Philatelic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution. It is now displayed at the National Postal Museum (see http://postalmuseum.si.edu/collections/object-spotlight/autographed-airmail-envelope.html)

While President Wilson posed for pictures, talked to officials and discussed the flight with Lieut. Boyle, Maj. Fleet and his crew positioned the plane for its 11:30 a.m. takeoff.

All eyes were on the Jenny. Sgt. E. F. Waters yanked on the propeller blade to start the engine. Nothing. He tried again… nothing. Several more attempts were made without success. The engine would not turn over. They checked the fuel gauge. It read full. A mechanic cleaned the spark plugs, but still there was no ignition.

Eyewitness reports depict President Wilson as irritated. Someone said they overheard him tell the First Lady, “We're losing a lot of valuable time here.” Whether or not these accounts are reliable is uncertain, but as the minutes passed beyond the 11:30 a.m. scheduled departure time, postal and military officials responsible for the new airmail service must have been embarrassed in front of President Wilson and the large crowd assembled on the Polo Field.

Capt. Lipsner or Maj. Fleet (or someone else) soon realized that the plane's fuel gauge was designed to provide an in-flight reading when the plane was level. With the plane in a tilted starting position, the gauge inaccurately showed full. It is hard to imagine that this anomaly of the Jenny's fuel gauge was never noticed before, under other circumstances.

The crew was ordered to refill the tank, but they discovered that there was no gasoline supply at the field. Which supervising officer was responsible for this oversight? Years later, the two aging veterans, Maj. Fleet and Capt. Lipsner, would argue over that question, each blaming the other.

After siphoning gas from other planes on the field and refilling 38262's tank, Sgt. Waters pulled on the propeller, and the engine came to life.

Lieut. Boyle revved the Hisso motor and began accelerating down the field. The plane slowly ascended and cleared the trees that surrounded the Polo Field. Spectators cheered and waved. At 11:46 a.m. (or 11:45 or 11:47, depending on which report is used), the first airmail from the nation's capital was in flight, ushering in an exciting new era of aviation.

The archived video footage of the ceremony and takeoff can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nhzmNvKY-i4

Capt. Lipsner watched the plane as it faded into the distance. Where is he going? he wondered. Lieut. Boyle was flying south.

For whatever reason, the first northbound airmail was flown in the wrong direction. Some would blame it on the novice pilot's inexperience or incompetence, while Lieut. Boyle and others said the plane's compass was unreliable, which was certainly true. The rudimentary liquid-filled compass used by Lieut. Culver and later donated by his widow is on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Image: © Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (A19680559000)

Minutes after takeoff, Lieut. Boyle landed once in a field to get his location, then took off. When he grew concerned that his bearings were still off, Lieut. Boyle tried to land again, but the field he chose was too soft, and his Jenny nosed over upon landing, causing the propeller to snap and damaging the cabane struts on the wings.

Lieut. Boyle, the upside-down Jenny and 140 lbs of mail he carried were stranded about 20 to 25 miles south of the Potomac Park Polo Field, near Waldorf, Md. By coincidence, the field Lieut. Boyle crashed in was near the home of Second Assistant Postmaster General Praeger.

Shortly after crashing, Lieut. Boyle called Maj. Fleet by phone to notify him of the problem, and then found someone to drive him back to the airfield. Lieut. Boyle and the mailbags returned to Potomac Park, and mechanics were sent to repair the plane. It was flown back to Washington that night and arrived at 8:05 p.m.

Newspapers reported the mishap the next day. Under the headline “FIRST AIR MAIL IN WASHINGTON IN 200 MINUTES”, the New York Times ran a smaller headline, “Flier Bound from Washington Lands in Maryland.”

Image: Smithsonian National Postal Museum

Southbound Flight from New York to Washington via Philadelphia (15 May) – The southbound New York-to-Philadelphia flight was scheduled to depart Belmont Field at 11:30 a.m. with Lieut. Torrey H. Webb flying Jenny 38278 and carrying 144 lbs of mail, comprising 2,457 letters plus packages and newspapers.

Among the letters was one from New York Postmaster Patten to President Wilson and Postmaster General Burleson, congratulating them on the inauguration of airmail service.

There was also what the New York Times described as “the first letter postmarked for air delivery” from Governor Charles S. Whitman, assuring President Wilson of the state's support for the forthcoming Red Cross fundraising campaign.

When Lieut. Webb touched down at Bustleton Field in Philadelphia, after flying approximately 90 miles from New York, he became the first pilot to complete a flight for the new U.S. airmail service. The letters he carried, bearing the “New York” version of the special airmail datestamp, are the true “Firsts” of “First Trip” letters from this historic event.

From today's perspective, one would expect that accurate records of these inaugural flights would have been made, and various contemporary and later historical accounts would correlate to the record. However, as usual for these early airmail flights, contemporary reports are filled with misinformation, and there are discrepancies among different accounts of the departure, arrival and flying times of the southbound flights by Lieut. Webb (New York to Philadelphia) and Lieut. Edgerton (Philadelphia to Washington).

Most New York-based sources report Lieut. Webb taking off from Belmont precisely at the scheduled 11:30 a.m. departure time. The New York Times story (16 May) with the “200 minutes” headline reported that Lieut. Webb took off at 11:30 a.m. and arrived in Philadelphia at 12:30 p.m., and that Lieut. Edgerton landed in Washington at 2:50 p.m. The same story reported that the two pilots flew a total of 200 minutes after “deducting the six minutes' intermission” at Philadelphia, but this account conflicts with other more reliable reports, and it even has internal inconsistencies.

Lieut. Webb’s Pilot's Daily Report records his takeoff from Belmont at 11:29 a.m. and arrival at Bustleton at 12:58 p.m., for a total of 1h29m flying time (89 minutes), somewhat longer than average for this leg.

Lieut. Edgerton's logbook records his takeoff from Bustleton at 1:14 p.m, his arrival at Potomac Park at 2:50 p.m., and the total flight time for this leg of the trip was 1h36m (96 minutes).

The pilots’ official records must be considered extremely reliable, and Lieut. Edgerton’s 2:50 p.m. arrival in Washington is corroborated by all sources. Based on their reports, the total flying time was 3h5m (185 minutes), with and additional 16 minutes between relay flights at Bustleton (201 minutes from start to finish).

Therefore, the New York Times “200 minutes” reporter must have been in error when he calculated flying time for Lieut. Webb at 60 minutes and Lieut. Edgerton at 140 minutes, excluding the bag transfer time of six minutes.

The Philadelphia Evening Ledger (15 May) reports Lieut. Webb arriving at Bustleton at 1:00 p.m. after a 75-minute flight (1h15m). That would point to an 11:45 a.m. departure from Belmont Field, fifteen minutes past the scheduled time and other reports, including Lieut. Webb’s own record.

The time between Lieut. Webb's landing and Lieut. Edgerton's takeoff, during which the mailbags were transferred from Jenny 38278 to 38274, is reported variously from six minutes to nine minutes, but it must have been about 16 minutes. One possible reason for a longer-than-usual transfer time in Philadelphia is that the mailbags Lieut. Webb carried in Jenny 38278 had to be ceremoniously turned over to the Philadelphia postmaster.

With the crowd of dignitaries and spectators watching, Lieut. Webb handed the mailbags to Philadelphia Postmaster John A. Thornton. The “through” mail (460 pieces) was loaded onto Lieut. Edgerton's Jenny 38274. The mail for Philadelphia and points serviced by its post office (182 pieces) was in a separate bag that was immediately given to the mail clerk for transport by truck to the distributing office.

After Lieut. Edgerton took off from Philadelphia at 1:14 p.m. and was en route to Potomac Park – probably sometime between 1:30 p.m. and 2:00 p.m. – orders were telephoned from the Washington-Potomac Park airfield, instructing Lieut. Culver, who was waiting at Bustleton, to fly the Philadelphia mail north to New York, rather than wait for the Washington mail from Lieut. Boyle's crashed plane.

At 2:15 p.m. Lieut. Culver flew north from Bustleton, carrying a mere 20 lbs of mail, comprising 200 pieces for New York City and 150 addressed to places served by the New York distributing office. Lieut. Culver flew Jenny 37944, which must be the plane that Maj. Fleet flew south from New York to Philadelphia on 14 May.

Curiously, Lieut. Edgerton's logbook entry for the 15 May flight from Bustleton to Washington states that his mail load was 20 lbs, but obviously that entry is incorrect. Lieut. Edgerton carried 136 lbs of mail, the net weight after mail was removed and added to Lieut. Webb's 144 lbs carried from New York. Lieut. Edgerton was evidently told the wrong amount when he made his logbook entry.

While Lieut. Culver was in the air north of Philadelphia, Lieut. Edgerton began his descent toward the Potomac Park Polo Field. Some of the people who had gathered for the morning departure of Lieut. Boyle's plane remained on the field to witness the arrival of the first airmail delivered to the nation's capital. Lieut. Edgerton touched down at 2:50 p.m., twenty minutes behind schedule.

Lieut. Edgerton's younger sister, Elizabeth, who had come with their mother to congratulate him, presented her brother with a bouquet of roses, and the two posed for a photograph. In this historic image, the young pilot is beaming with pride as he stands with his kid sister in front of the Jenny. Lieut. Edgerton would eventually achieve the best record among the original U.S. Army airmail pilots.

The special airmail postal truck transported the 136 lbs of mail from Potomac Park to the main post office. From there, nearly 200 Boy Scouts on bicycles delivered letters addressed to local residents – special delivery service was included in the 24¢ airmail postage – while letters for other places were sorted by clerks and sent on their way.

Northbound Flight from Philadelphia to New York (15 May) – In her account of the first airmail flights, Lieut. Culver's wife claims that he was deeply disappointed when the call came from Washington, informing him that Jenny 38262, the plane he had flown from New York to Philadelphia the night before, had crashed and would not be available for him to fly to New York with all of the northbound mail.

Instead, Lieut. Culver flew in plane 37944 with 20 lbs of Philadelphia mail, comprising 200 letters for New York City and 150 addressed to places served by the New York distributing office. At 2:15 p.m. – more an hour behind schedule – Culver took off from Bustleton, bound for Belmont Field.

Around 3:30 p.m., as Lieut. Culver approached Belmont Field, he was joined by two planes that had taken off from the nearby Hazelhurst airfield, and they flew in formation for the final approach. Lieut. Culver landed at 3:37 p.m. and was greeted by a crowd of onlookers who pushed forward, dangerously close to his moving plane.

Image: © National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution (A-5388-A)

With the band playing “The Star Spangled Banner,” and the crowd cheering and waving American flags, the mailbag was removed by a postal employee, Harvey L. Hartung, and put on a truck bound for the nearby Long Island Railroad station. From there a special train carried it to the Pennsylvania Station Post Office.

By the end of Wednesday, 15 May 1918, the first day of regular airmail service had produced mixed results. The southbound flights had gone smoothly, with the mail for Washington arriving at 2:50 p.m., only 20 minutes late. The arrival of the northbound plane in New York was celebrated as a historic event, even if it was more than an hour late and the Washington mail was missing. Newspapers reported the misadventures of Lieut. Boyle and the missing Washington mail, but the press and the public were generally forgiving, recognizing the challenges of airplane navigation at this time.

16-17 May 1918 – More Problems

Back to TopOn day two of the new airmail service, Jenny 38262 was grounded for repairs in Washington, D.C. Lieutenants Edgerton and Boyle were also there with 38274, which Lieut. Edgerton had flown with the mail the previous day. Lieut. Webb was in Philadelphia with Jenny 38278. Lieutenants Bonsal and Culver were in New York with 37944, which Lieut. Culver had flown with the mail from Philadelphia to New York the previous day.

The two planes that were not flown in the 15 May relay – 38275 and 38276 – were presumably still at Hazelhurst or Belmont at the end of the first day. Lieut. Miller evidently flew one of the Jennys (probably 38275) from New York to Philadelphia before the afternoon of 16 May, but the exact time of his flight is not currently known.

Northbound Flight from Washington to New York via Philadelphia (16 May) – The undelivered Washington mail from Lieut. Boyle's crashed Jenny was carried on the second day of service, and both dates – 15 and 16 May – are considered to be First Trip mail. In fact, the words “First Trip” were reinserted into the special datestamp with the 16 May date and used to postmark some of the mail.

The airmail letters deposited at the Washington, D.C., post office after 11:00 a.m. Wednesday, up to and including 11:00 a.m. on Thursday (16 May), were postmarked and added to the mail brought back from Lieut. Boyle's wrecked Jenny 38262. Evidence that the 16 May 11:00 a.m. timestamped mail was flown on that day is a cover with a 16 May 4:30 p.m. receiving backstamp. All of this mail was flown north from Washington by Lieut. Edgerton on Jenny 38274.

Once again, misinformation and conflicts between sources make it difficult to provide a definitive statement concerning the number of pieces and total weight of the first airmail to reach New York from Washington on 16 May 1918. However, the northbound flight from Washington to New York via Philadelphia was successful, and the flight times reported are accurate.

The New York Times (16 May) reported that Lieut. Boyle received “four sacks of mail” on Wednesday (15 May), including “three for New York and one for Philadelphia, weighing in all 150 pounds.” Other reports stated that Lieut. Boyle carried 140 lbs of mail on this unsuccessful trip.

The next day's Washington Herald (17 May) reported that Lieut. Edgerton flew from Washington on 16 May carrying “7,360 pieces of mail for New York and 570 for Philadelphia” (total 7,930 pieces). According to the same article, “Of the New York mail 3,630 pieces were for delivery in New York City, and 3,739 for distribution in New York State and New England” (there is a slight discrepancy of nine pieces). This large load comprised the original mail received for the 15 May crash flight and the additional mail posted in Washington after 11:00 a.m. on 15 May, up to 11:00 a.m. on 16 May.

According to the New York Times report (17 May), Lieut. Edgerton took off from Washington-Potomac Park at approximately 11:35 a.m., but did not land at Philadelphia-Bustleton until 1:35 p.m. Lieut. Egerton’s own report states that he took off at 11:25 a.m. and arrived at 1:33 p.m. The flight time of more than two hours was unusually long.

The delay was attributed to Lieut. Edgerton's approach at a high altitude of 8,000 feet, which caused him to fail to see the markers on the hangar at Bustleton Field. After overshooting the mark, he circled back and landed. The article noted that if he had landed on his first pass, Lieut. Edgerton would have made the trip in 1h40m (landing at 1:15 p.m.).

The same article reported that the mailbags were quickly transferred to Lieut. Webb's plane and in three minutes he took off for New York, at 1:38 p.m. The number of the Jenny that Lieut. Webb flew north on 16 May must be 38278, the plane located at Bustleton at the end of the first day of flights.

Lieut. Webb's Jenny came into view at Belmont airfield at 2:55 p.m., and he landed at 2:58 p.m. According to the New York Times (17 May), he carried “118 pounds of mail from Washington and 5 pounds from Philadelphia, a total of 3,490 pieces,” but this conflicts with the Washington Herald report (17 May) that there were 7,369 pieces of mail bound for New York on board with Lieut. Edgerton when he left Washington.

Attempted Southbound Flight from New York to Philadelphia (16 May) – A serious crash landing marred the second day of airmail service on Thursday, 16 May. This time, it was the southbound plane from New York to Philadelphia, with Lieut. Bonsal at the controls.

The New York Times (17 May) commented that Lieut. Bonsal was flying a “new airplane.” The Pilot's Daily Report left the number blank. However, evidence suggests that the plane Lieut. Bonsal crashed was number 38276. The photograph of the wrecked plane does not show the number clearly. However, it does show that there was only one pilot’s seat, with a mail compartment in place of the forward seat. The 1919 report by Second Assistant Postmaster General Praeger lists 38276 with relatively low mileage and flying time (3,401 miles, 51h34m), which indicates the plane was out of use for a period of time.

Based on a compilation of accounts, Lieut. Bonsal took off from Belmont at 11:29:30 a.m. with 17 lbs of mail (237 pieces). Lieut. Bonsal had been instructed not to fly below 5,000 feet for 40 minutes. Steering by compass in foggy conditions and running low on fuel at 85 mph, Lieut. Bonsal realized he should have been close to the airfield at Bustleton and was off course.

At approximately 1:10 p.m. he located a suitable landing field at the Bridgeton Fairgrounds Race Track at Bridgeton, N.J., about 150 miles south of New York and 40 miles south of Philadelphia. Lt. Bonsal's first attempt to land was thwarted by a herd of grazing horses. On his second attempt, the plane struck a fence. The propeller was smashed and one of the wings was badly damaged, but the pilot and mail were unharmed.

Image: Smithsonian National Postal Museum

According to an article in the Bridgeton Evening News (18 May), Lieut. Bonsal “was badly shaken and nervous but was not injured except for a cut on his hand.” The pilot was quoted as saying “he had used this machine but once before, having had a trial trip of about twenty minutes the night before” (source: njpostalhistory.org/media/archive/180-nov10njph.pdf).

George R. Elwell, a local rural mail carrier, drove Lieut. Bonsal and the mailbags to the post office. The mail was taken to Philadelphia on the 3:05 p.m. train, and later that evening the Jenny was trucked to Bustleton.

At 5:45 p.m. Lieut. Miller took off from Bustleton with the New York and Philadelphia mail for Washington, probably in 38275, which he would have flown south from New York (without mail) sometime earlier in the day. About 25 miles out, Lieut. Miller experienced engine trouble and turned his Jenny around. After Lieut. Miller's return to Bustleton at 6:30 p.m., Lieut. Edgerton volunteered to take the mail in Jenny 38274. He took off from Bustleton at 6:40 p.m., and he arrived at Washington, D.C., at 8:30 p.m.

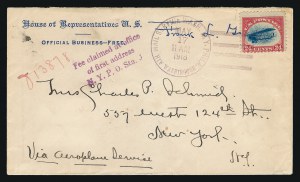

Shown here is a rare cover carried from New York on the 16 May southbound flight that crashed at Bridgeton, N.J., and a mail facing slip that accompanied the letters from Philadelphia to Washington that were flown by Lieut. Edgerton on 16 May.

Image: Siegel Auction Galleries

Attempted Northbound Flight from Washington to Philadelphia (17 May) – The third day of airmail flights – Friday 17 May – presented Lieut. Boyle with another opportunity to fly the mail from Washington to Philadelphia, but again he veered off course in the same Jenny, number 38262, and crashed the plane before reaching Bustleton Field.